On June 13, 2002, David Clohessy stepped into the light of history. A former altar boy in a rural Catholic church in Moberly, Missouri, he stood at a podium in a massive hotel ballroom in Dallas — and staring back at him from row up upon row of tables, packed into the room ten-deep, were some 280 Catholic bishops.

Many in that audience were already familiar with Clohessy as the national director of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, the country's longest-active support group for victims of clergy abuse. Clohessy had spent years trying to grab the bishops' attention.

Indeed, Clohessy seemed to be quoted in every other newspaper story about a predator priest going back to the early 1990s. He'd show up at churches with fliers listing support group meetings for victims, and he'd prod reporters to cover the protest. He held press conferences with tearful victims announcing lawsuits. He insisted on calling accused priests "perps."

He was, in a word, a nuisance to the Catholic Church. And until that moment in 2002, that's all he had ever been.

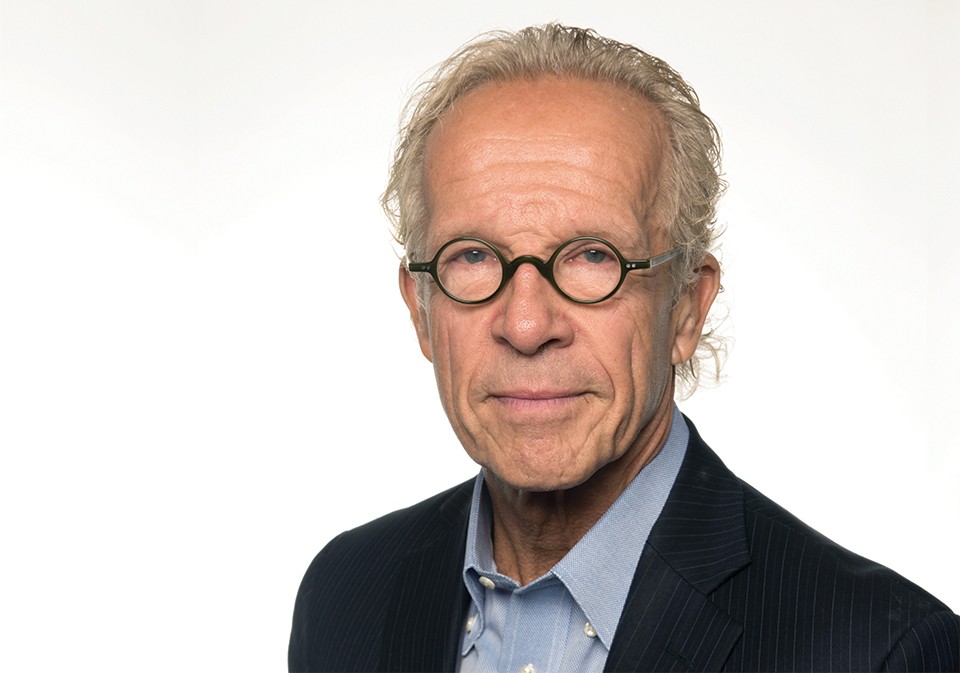

That day, with his square-framed glasses slightly askew and his outfit of a simple gray suit and white shirt, the SNAP director looked more like an accountant than the radical victims' rights advocate. But this meeting of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops was focused specifically on the exploding clergy abuse scandal — and it had drawn the eyes of the world.

After a smattering of applause, Clohessy began his speech. From almost the moment he opened his mouth, even before describing the local priest who molested him as a boy, he started to cry.

"I've been encouraged to talk about my personal experience, being molested, sodomized by Father John Whiteley in the Diocese of Jefferson City, and the effects it's had on my life," Clohessy said. "I could describe nights curling up in the fetal position and sobbing hysterically while my wife Laurie simply held me, and having to get up and change the bedsheets because they were soaked in tears. I could talk about nightmares, depression, sexual problems. About how, even now, almost every day I fundamentally somehow feel like a fraud."

But whatever self-doubt Clohessy's trauma left in him, the emptiness and pain, there was no hesitance in his voice when he addressed the bishops about their role in the coming reckoning. He addressed them as "smart men" who "know the right thing to do."

"Fundamentally, it's simple. What causes sexual abuse? That's complicated. How to begin to treat these men or cure them? That's complicated. What to do when an abuse survivor walks in your door?

"Gentlemen," Clohessy said, "I submit to you, it is not complicated."

Even for Clohessy, who is fond of rhetorical flourishes, his message to the bishops still stands as an almost too-perfect shot of understatement. In reality, no scenario has been more fraught with moral, religious and legal complexity than the moments after a survivor brings their story to a church official. For years, Clohessy had been trying to convince the public that the church's typical reactions — the blunt denials, secretive settlements and retaliatory lawsuits — were, as he put it in the speech, like applying a "dirty bandage" to an "infected wound."

This was the dawning of the era of the investigations chronicled in the 2015 movie Spotlight, as the Boston Globe began publishing the stories that would not just reveal a systemic cover-up of clergy abuse in Boston, but the entire United States. The stories would win the paper a Pulitzer Prize in 2003 and usher in a new era of greater scrutiny and accountability.

Eighteen years have passed since that day in Dallas. Despite Clohessy's pronouncement of simplicity, the subject is as complex as ever.

For SNAP, an organization that had for years thrived with a tiny and nimble staff, its recent history has been defined by multiple lawsuits and internal strife. The hits came in a rattling sequence during a span of six months at the end of 2016. SNAP, which was no stranger to being sued by priests, was taken to civil court by one of its former employees who accused it of running a kickback scheme with attorneys; then SNAP announced it had reached a defamation settlement with a priest it had once labeled a "cunning predator."

Finally, adding organizational injury to legal insult, SNAP lost its triumvirate of officers in a wave of resignations, starting with Clohessy.

SNAP's longtime critics in the Catholic world cackled, and even mainstream outlets ran stories that linked the resignations to the organization's run of controversies. At the time, the story appeared to be a simple one: SNAP fought the church, it spent several years getting walloped, and now it was crushed.

One of Clohessy's longest allies, clergy abuse attorney Jeff Anderson, believes there's truth to the notion that in SNAP's lowest moments, its opponents took the upper hand.

"The Catholic bishops had the resources and ability to overwhelm SNAP. It was a mismatch," he says, adding, "Goliath slayed David."

The funny thing is, David Clohessy never really went away.

In a series of wide-ranging interviews earlier this month, Clohessy sat down with the Riverfront Times to reflect on a career in survivor advocacy that, at least for the moment, is in something he calls "a dip."

That's one way to describe it. In the past three years, Clohessy says he's undergone several trips to the emergency room, four surgeries and 30 sessions of chemotherapy.

These days, most of Clohessy's activism is confined to a two-story home at the back of a quiet cul-de-sac in St. Louis' Ellendale neighborhood. On a recent afternoon, a circular wooden table in the dining room is covered with the accessories of his ongoing work. There's a laptop, several newspapers and an apparent explosion of incongruous printouts and notes. Underneath some of those notes is a large planning calendar with a date marked for an upcoming MRI. Another pile of papers hides a small plastic basket filled with pill bottles.

When I tell Clohessy about Anderson's metaphor that compares him to David getting stomped by a Catholic Goliath, he laughs.

"Oh, yeah, yeah," he says, chuckling through his sarcasm. "The church gave me cancer! And it gave me a brain tumor!"

It had started with throat cancer. Then came a second diagnosis, for prostate cancer.

"Actually," Clohessy now clarifies, "the third thing I got was a brain tumor, in that order." His tumor is non-cancerous, which is doubly significant as it was a brain tumor that cut short the life of Clohessy's older brother Brian in 1993.

Clohessy is 63 now. He's focusing on his health, working out at the local YMCA every day and continuing to see doctors to monitor his cancers. If he had energy, he says, he would still be on the road, pulling 60-hour weeks and hounding state investigators to keep the pressure on Catholic bishops.

But he's tired. For the first time in his life, he can't get through a day without a nap.

When Clohessy stepped down as SNAP director in December 2016, he insisted that his health was the driving motivation for leaving a role he'd held for nearly 30 years. He adds now that it was his emotional health as well. In the last five years of his directorship, SNAP had faced two major legal attacks by priests, in Kansas City and St. Louis, and both sought a judge's order to allow them to access the network's library of survivor statements and documents.

To Clohessy, it was a dire reversal. "In a very short period of time, a group that had spent its history playing offense was suddenly having to play substantial defense," he says. "There was real thought that we were not going to survive."

But they did, and now, thanks to medical intervention, Clohessy has survived his own brush with an existential threat. He's now technically a volunteer spokesman for SNAP.

Still, after a lifetime of running, it feels strange to stop and take a breath.

"I have a dismal track record of predicting the arc of my own life," Clohessy admits — but unlike Anderson's biblical metaphor, he doesn't see that arc as one of defeat.

"If this were somehow a battle to crush or hurt the church, then yeah, we're losers," Clohessy concedes. "But that's never what this has been about."