DEFINING PREJUDICE

At City Garden Montessori in the Shaw neighborhood, We Stories' twelfth cohort comes together on a Sunday afternoon in March to listen to a few more books.

"The theme of today is what comes next," Lancaster says, following a rousing guitar singalong in the elementary school's multipurpose room.

The 50 or so families disperse: toddlers and their parents to the gym to page through board books and play with baby dolls of various hues, while herds of preschoolers move into classrooms for a story-centered activity, their parents left to themselves for some adult discussion.

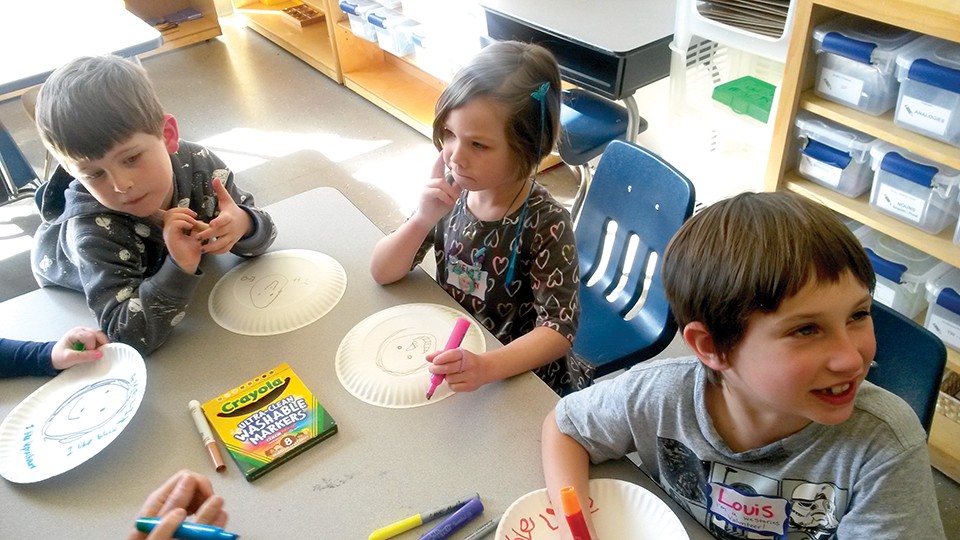

In one classroom, about a dozen four- to six-year-olds listen to Mae Among the Stars, a picture book about a young Mae Jemison, the first female African American to travel into space.

Volunteer Beth Doht explains the word prejudice to the exuberant crew as they blurt out what it might mean, "how our outsides don't always tell us about our insides." Then they get to work crafting self-portraits on paper plates, carefully examining each Crayola Multicultural crayon to find just the right shade.

Meanwhile, Mary Lamboley of St. Louis County sits at a table with other parents, trading advice about how to answer kids' questions about race, where to find information and how to diversify friendship groups.

Lamboley talks about reading her son his favorite book, a story about a police officer, over and over before realizing that every character in it is white.

"He would see black people and say, 'That's a scary person.' I didn't realize I was perpetuating those beliefs by where I lived, what I read, our habits and patterns," she says. Growing up, "race was basically about 'what are we going to do about those poor kids in Africa?'"

Lamboley knew she needed to learn more. She went through Witnessing Whiteness and became a facilitator. We Stories helped her find ways to name and celebrate differences with her son, she says.

And it was also about the fun of discovering new favorite books.

Her son, Theo, skips over to the table, helps himself to a bag of popcorn and snuggles into his mom's lap. The five-year-old, a NASA fan wearing a sweatshirt printed with astronauts, tells his mom the best part of the story he heard was when Mae rocketed into space.

DEVELOPING CURRICULUM

On a different weekend in March, eight educators convene in the Creve Coeur home of Angela Kelly, a reading specialist in the Ladue School District.

Kelly and Rachel Morgan, who works at the Children's Community Microschool, have gathered teachers for their inaugural advisory session to evaluate a prospective Community Conversations curriculum.

The two women have spent the past eighteen months compiling resources to help white third- through eighth-graders learn about the history and implications of race in the U.S. They wrote it to adapt to multiple settings, including after-school groups, church and community organizations or even regular classrooms.

The advisory group combed through lessons on identity, but they weren't the first to provide input. Kelly and Morgan had already spoken to the YWCA's Ferguson and We Stories' Horwitz, members of Educators for Social Justice and an early childhood group.

They want to get it right before launching a pilot in the fall.

"We welcome all feedback, especially the stuff that's hard to hear," Morgan, 43, tells the group.

The four-part curriculum begins by looking at artwork and poetry by people of color, such as Cbabi Bayoc, a St. Louis artist and illustrator.

One teacher suggests using paint samples for a lesson on skin tones. Another questions whether children will know what "mottled" means.

At the next meeting, they plan to dive into history lessons, from before enslavement through the civil rights movement, acts of oppression and resistance, the Trail of Tears, the Harlem Renaissance and Japanese internment. It's a history many white children don't know, Morgan says.

The hefty topics are necessary, says Kelly, 50, who is a Witnessing Whiteness alum. "I felt like I had gotten so much from being in a group with white people and I wanted to do that for children.

"Our ultimate goal is that the white children who have participated in the Community Conversations will feel comfortable in engaging in these conversations with people of color. We hope it leads to action in anti-racist ways."

That action can take many forms, says Hunter, the program founder. It's voting. Speaking up. Being thoughtful about where you spend your money. Advocating at your school or workplace.

"The truth is still a struggle, but I'm overjoyed at the infinite possibilities," she says of her decade-long program. "I hope more things ripple off of it. There's so much work to do."

Editor's note: Due to an editing error, a photo caption referred incorrectly to Kira Banks' role. She analyzed data assessing the effectiveness of Witnessing Whiteness groups; she did not assist in forming We Stories. We regret the error.