Would anyone like to adopt the St. Louis County Pet Adoption Center?

It is about eight years old, filled with adorable animals, and its current owner, the county's Department of Public Health, is looking more and more like it doesn't want the hassle that comes with directing one of the largest open-admission animal shelters in the region.

Outside the low-slung building in Olivette, dog walkers crisscross the sidewalk on their way out of the shelter parking lot. The dogs strain on their leashes, noses to the ground, their legs set at eager angles as they use this brief time outside their kennels to investigate odd rags and interesting leaves.

In a typical month, the shelter takes in more than 300 animals. Staff members say the shelter often reaches double its effective capacity, but, until recently, officials and shelter board members defended the facility's operation by pointing to the only statistic that seemed to matter: the euthanasia rate.

In 2011, when the shelter opened, pounds were being phased out in favor of an animal control model that emphasized adoptions rather than the quick and fatal disposal of strays. At first, the shelter euthanized about half the animals in its care every year. But that rate was down to 22 percent by 2017. At the beginning of 2018, the rate hit single digits, a venerated benchmark in the animal welfare world that is often associated with "no kill" shelters.

It was a notable achievement — and it had political ramifications. Then-County Executive Steve Stenger had made the county's euthanasia rate a key issue in his 2014 election campaign. After he won, he moved the Animal Care & Control division under his office, adopting the shelter — and the credit for its plunging euthanasia rates — as his own.

And indeed, the euthanasia rate kept falling. Or, at least that is how it appeared.

The last two years have seen the shelter staggered by scandal. First, its once-heralded director was fired after she was accused of bullying staff and making racist comments. Her termination was followed by the release of an audit that exposed the misleading nature of the shelter's past euthanasia reporting.

Today, the shelter's celebrated, euthanasia-lowering successes have been revealed as a statistical sham. Stenger is in federal prison for separate crimes. The future of the department of Animal Care and Control is uncertain. The shelter is at a crossroads. All paths seem to pass through crisis.

Even in the shadow of scandals, multiple shelter employees who spoke to the Riverfront Times insist that hiring a competent director and stabilizing a staff that is fearful of losing jobs would make all the difference. Instead, the Department of Public Health is toying with the idea of ditching the whole mess through privatization of the shelter.

If that happens, it will not be without a fight over who is responsible for the dysfunction. In interviews with the Riverfront Times, employees, volunteers, and county officials offer clashing viewpoints of who deserves the most fault, with staff blaming county officials, volunteers blaming staff and county officials blaming both everyone and no one.

For all the finger-pointing, the question is: Where does the shelter go from here?

"We're the redheaded stepchild of the county," one shelter staff member tells RFT, summarizing the predicament. "No one wants us."

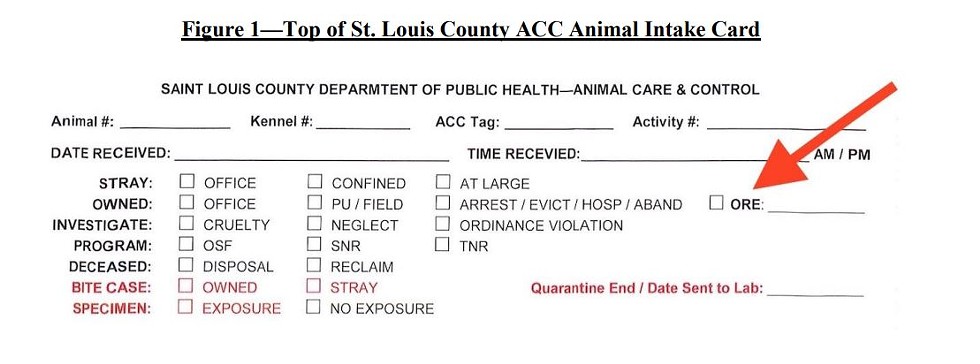

Three tiny letters — "ORE" — were the key to a statistical smokescreen that concealed the true numbers of animals killed at the St. Louis County Pet Adoption Center.

The letters appeared innocuously above one of the many boxes on the shelter's intake forms. Most people seemed to barely notice as they said their emotional goodbyes in 2018 to their suffering pets.

"I think 75 percent of the people who came in were not thinking straight," recalls one former shelter employee, who spoke to the Riverfront Times on condition of anonymity to describe his time as an intake worker.

"These were people upset about having to give up the dogs. They would sign whatever you asked them to sign."

But that one box, floating off on the right side of the page, was crucial. The staffer says a supervisor pointed the ORE box out to him during the training, specifically directing him, to "get them to initial this" during the intake process.

"I was being told about 30 different things that day," he says, "so I didn't question it."

He did get people, lots of people, to sign it.

Like other employees, though, the ORE proved impossible to ignore forever. It stood out even among the other issues, like the horrible rumors heard about the last director, Beth Vesco-Mock, who had been fired shortly before his hiring. The shelter had "chronic understaffing," he says, an obstacle made worse by a group of shelter volunteers who, in his view, "only wanted to complain."

"People were there because they loved animals, which was great," he recalls, and it was that force that united the shelter's factions, bonding them to an overriding goal: "To euthanize as few animals as possible."

As he'd later come to understand, though, that goal had twisted the shelter's intake procedures in strange ways. When he finally asked his supervisor about the ORE box, and why he was being pressured to get it signed in every intake, he wasn't prepared for the answer. He was informed that ORE meant "owner requested euthanasia."

"I wasn't thrilled about it," he says now. "Because they weren't all requesting it. I went to my supervisor, and she told me, 'Oh it's just a policy, you don't have to do it.' And I said, 'Are you sure?'"

There are conflicting accounts of how and when the shelter's ORE policy originated. At times, it seems it was applied inconsistently. A second shelter staff member, who worked in various departments since 2018, recounts that she knew of intake representatives who simply ignored the ORE requirement or allowed people to decline initialing the box.

"If someone really had a problem with signing the ORE, we were like, 'It's OK, you don't have to sign it,'" she says. "Because we can't force them to sign it."

They would be ordered, though, to try. After the firing of the shelter's director in March 2018, multiple employees tell RFT that the shelter's leadership, helmed in the interim by a Stenger policy advisor, continued to aggressively push the ORE policy. When intake representatives complained about the ORE to their supervisors, they were given a new directive.

"Our supervisors were saying, 'We have to do it. You do it or you lose your job.'"

It wasn't until July 2019 that an independent audit exposed the ORE policy for what it really was: a strange kind of fraud, one that obscured — and, in a way, laundered — the shelter euthanasia rate that was reported monthly to the county executive and shelter advisory board.

The ploy hinged on abusing the "ORE" intake category, one intended for animals whose age or medical conditions left only one option. Typically, ORE cases are rare: The audit, conducted by California-based Citygate Associates, surveyed 28 other government-run animal shelters across the country, and found that ORE cases made up just 2.8 percent of total outcomes. St. Louis County's animal shelter had five times that rate, with 14 percent of all animals passing through the front doors being marked for "owner requested euthanasia."

It was more than the shelter data that convinced auditors something was amiss. One dog, a husky mix designated for ORE at intake, "was surrendered by his owner on 1/16/19 due to a noise ordinance violation," and then euthanized after 27 days in the shelter, auditors found. Another ORE dog, a pit bull returned for being "disobedient," stayed in the shelter 55 days before being euthanized for "behavioral reasons."

In at least one case, the audit noted that a woman turning in a dog specifically asked that her dog would not be euthanized. "She checked and initialed the ORE box as directed by staff, but Citygate did not hear her being told what the ORE initials actually meant."

It was this category of animals — dogs and cats whom the shelter seemingly tried to adopt out, and then, failing that, moved to euthanize — which did not belong as ORE. That was critical: The shelter reported only its "shelter decision" euthanasias to its higher-ups. ORE cases, though, are not considered "shelter decision," and so became the shelter's statistical dumping ground.

The ORE scheme was brilliantly effective. The audit found that while the shelter reported 602 "shelter decision" euthanasias to its advisory board in 2018, its ORE euthanasias had climbed to 645 cases — in other words, the majority of the shelter's euthanasias that year.

Some staff members complained, while others put their head down, fearful of making waves.

"That was why the policy was put in place, so it didn't look like you'd done euthanasias," the former intake staffer says. "Their desire to keep animals from being euthanized, which is a good desire, was taken to very odd extremes."

On September 19, eight members of the St. Louis County Animal Advisory Board take their seats for its monthly meeting, the same one that has been convened every month since 2015. Empowered only to advise the county executive, the present members have no direct control over the shelter, and so they play the dual roles of watchdog and supporter.

At this meeting, the board faces the truth of the shelter's euthanasia policy.

The place of the shelter within the structure of county government has shifted. In late 2018, Stenger returned the department of Animal Care & Control to its former home, the Department of Public Health. The change brought a new acting director, Spring Schmidt, who had just been promoted, in yet another acting role, as director of the entire St. Louis County Department of Public Health. And it is Schmidt who has the task of answering for the shelter's dysfunction.

She begins by delivering updates about the shelter audit released in July. The final report, which came to 184 pages of scathing analysis, shook the shelter.

The shelter, according to the audit, "is so crowded at times that no empty cages can be found in the regular intake/stray rooms," requiring "healthy new animals" to be housed along with the sick. Errors during the intake process led to "incorrect hold periods, ages, breeds and sex." The audit found that the basic movement of animals through the shelter "is currently a confusing, haphazard process," observing that "not only was there no sense of urgency observed to move animals out of the shelter expeditiously but numerous bottlenecks, problems, and issues existed that made animals stay in the shelter much longer than necessary."

The auditors corroborated many of the worst rumors and offered more than 150 recommendations for the shelter to implement. So far, according to a packet handed out at the meeting, the shelter has completed around 50, including ending the ORE policy, eliminating the use of bleach and hiring a contractor to split an outdoor play area into two yards.

Schmidt's remarks on the audit are blunt. Supervisors have to be retrained, she says, "on what it means to be a supervisor." She blames the recent "disinvestment in the chain of command," and the fact that the shelter is on its third director in three years.

A career government manager, Schmidt spent most of the last ten years in the county's Department of Public Health as a health education supervisor. As acting director of public health, she's in charge of more than 70 divisions and a budget in the tens of millions. Her duties also include running the embattled, audit-targeted animal shelter.

Some things changed quickly, like the ORE policy, which Schmidt refers to as "statistical manipulation." After she was alerted to the issue, she says her office put a stop to requesting euthanasia as a default part of the intake process. Following the audit's recommendation, the shelter updated the intake paperwork to remove the much-abused ORE box.

But that also meant, of course, that the shelter would update how it counted its euthanasia statistics, meaning that, for perhaps the first time in years, the advisory board would see an unmanipulated number next to the spreadsheet field for "Euthanasia Rate — Shelter Decision."

Indeed, the August 2019 euthanasia number is high. Very high. It is unlike anything the advisory board has seen in two years, with the "shelter decision" euthanasia rate coming in at just over twenty percent. That was double the previous month's tally. It is the highest euthanasia rate reported since 2017.

"This is the first time that we really see a change in the calculation as far as our euthanasia rate going up," Schmidt informs the room. "That is the shelter decision, not a manipulation of ORE. The number is higher, and I did expect it to be higher."

Schmidt repeats that the shelter remains committed to lowering its euthanasia numbers while, again, avoiding "statistical manipulation."

"We can continue to drive it down, and not through statistics," she says. "We can drive it down through the actions that we take for the animals that are here."

But if the board members are reassured by Schmidt's confidence, it dissipates in a wave of frustration. The audit's mountain of recommendations cover every corner of shelter operation, from record-keeping practices to sanitation to infrastructure. Again and again, Schmidt responds to questions with variations of that most frustrating answer: "It's going to take time."

"You don't get audit recommendations like this without systemic breakdowns in culture and process and procedure," she says, and then, as if that wasn't clear, adds, "And everything else, too. It's really all of it. You don't get results like this unless it's breaking down at all of those levels."

About 40 minutes into the meeting, Pamela Hill, a professional cat behavioralist who now chairs the board, has heard enough about the virtues of patience. She has spent more than four years waiting for the shelter to right itself.

Hill wants to know what they can do "today" to ensure that fewer animals are euthanized.

"Where is the urgency?" Hill asks Schmidt from across the table. "Is today the day? Is tomorrow the day? Is it next Wednesday?"

Not for the first time, the issue of the staff failures takes center stage. If she were a shelter employee, Hill says, she would be coming into work five minutes earlier each day, "trying to make it less likely that some animal will be euthanized for behavior, aggression or whatever it is."

Board member Allison Burgess, who also sits on the board of Carol House Pet Clinic, charges that some employees lack the "compassion" needed to make the shelter a real "no-kill" force for animals.

"We talk about culture," Burgess says. "I worry that it's not going to happen until we have a leader in place. We need someone that is going to extol the virtues of putting compassion first, to put the animals first. That is just totally missing."

Roughly two years ago, in that same meeting room, the advisory board thought it had met just such a leader. She was experienced, had glowing references and was willing to move her family to Missouri from New Mexico to take the job.

Her name was Beth Vesco-Mock.

When it comes to the St. Louis County Pet Adoption Shelter Center, no person is more demonized and defended than Beth Vesco-Mock.

Hired by Stenger in September 2017, Vesco-Mock had spent the previous decade as the director of the Animal Service Center of the Mesilla Valley in New Mexico, where she had turned heads with her impressive results lowering euthanasia rates. As she told one local newspaper there, she had transformed a shelter from a "slaughterhouse" to one with "a culture of life."

From certain angles, Vesco-Mock was the perfect candidate for St. Louis County. She also seemed to tick the important boxes for Stenger, who sought to fulfill his 2014 campaign promise to lower euthanasia (and thereby wring more political capital from his supporters in the animal welfare community.) For members of the shelter's advisory board, who yearned for a director with genuine animal shelter experience, Vesco-Mock was exactly the sort of "animals first" leader they'd been waiting for.

At first, she seemed just as advertised: Almost immediately, the euthanasia rate plummeted, making Vesco-Mock allies on the advisory board. But the new director made a disastrous impression on the staff, and the accounts of one particular racist incident would follow her for months, ultimately sealing her termination.

Starting in early 2018, shelter volunteers and staff began contacting RFT to complain about Vesco-Mock. Amid allegations of mismanagement and overcrowding, multiple sources referenced details of an incident in which Vesco-Mock, they said, had told a group of black employees to get back to work and to stop "gangbanging."

One employee, who requested anonymity to protect his current position in the shelter, claims he witnessed the incident, which he says occurred during a kennel staff meeting "not long" after Vesco-Mock's hiring.

"I was part of that group," the staffer tells RFT. "We was all in the hallway, and she said, 'Stop gangbanging in the hallway.' She just said it. It was the wrong thing to say."

Afterward, the employee says, black staffers in the group discussed the incident, and "took offense."

"We all had this confused look. We weren't angry, but confused. We're colored people, and what she said, we just don't do that. That's how I took it. After that, people started quitting left and right."

In a matter of weeks, the "gangbanging" comment had hit the shelter's grapevine, and volunteers began emailing reporters and showing up at county council meetings to complain about the new director.

Harmony Collender, an animal caregiver at the shelter who was hired in early 2018, says her first impression of the workplace was that "no one liked" Vesco-Mock. Collender claims she witnessed the director going out of her way to "act disrespectful" to a supervisor, "just putting him down, in front of me, when he hadn't done something as quickly as she wanted him to."

Eventually, employees filed complaints against Vesco-Mock, leading to meetings with representatives of the county HR department. Similar complaints became weekly features at the county council meetings, where a core of activists and volunteers not only pleaded on behalf of the animals, but begged the county to save the staff from Vesco-Mock's racism and shelter mismanagement.

But Vesco-Mock had the support of Stenger, who seemed entirely pleased with his director's impact on the shelter.

In January 2018, the shelter reported a dazzling live-release rate of 97 percent, a newsworthy announcement that brought a KTVI (Channel 2) reporter and camera crew to document the shelter's animal-saving successes. The story featured Stenger praising the adoption numbers, with Vesco-Mock taking credit for changing the shelter's "culture."

"We made a culture change here," she explained, "from a culture of keeping them comfortable until they were euthanized, to keeping them comfortable until they find a home."

There was another side to Beth Vesco-Mock, a history she likely hoped to have left behind when she arrived in St. Louis.

But news travels, and one week after Stenger and Vesco-Mock made their televised victory lap around the shelter's live-release rate, RFT became the first local outlet to publish details on Vesco-Mock's scandal-scarred career as shelter director in Mesilla Valley, about 50 miles from the border in southern New Mexico.

In July 2017, after nine years running the Mesilla Valley shelter, Vesco-Mock surprised local officials by tendering her resignation. According to local news reports, the decision followed months of conflict, which had spilled into emotionally charged hearings before the city council. Earlier that year, a former employee had leaked photos of the Mesilla Valley shelter to local media, showing filthy conditions and sick dogs. Two weeks later, Vesco-Mock was caught in a different scandal, admitting that she had allowed a drug company to administer experimental diarrhea medication to some of the shelter's dogs. (She insisted it was standard practice and that no animals were harmed.)

And as in St. Louis, Vesco-Mock was accused of racism. According to the minutes of an April 2017 hearing held by the Las Cruces City Council, a former shelter employee charged that Vesco-Mock was a "racist, bigoted pig" who had driven away sixteen employees.

The summer of 2017 would be Vesco-Mock's last in New Mexico. One month after tendering her resignation at the Mesilla Valley shelter, she packed up her family and moved to Missouri.

For both for Vesco-Mock and St. Louis County's shelter, it was an opportunity to do something different. That opportunity ended in dramatic fashion when Steve Stenger fired her.

On February 27, 2018, Beth Vesco-Mock, accompanied by her private attorney, faced a hearing over her leadership of the shelter. For weeks, county council members had listened to volunteers and staff members describe a shelter struggling with overcrowding, disease and human dissatisfaction. Now they wanted to hear directly from her.

Vesco-Mock was not without supporters. At the hearing, two advisory board members spoke on her behalf, including Ellen Lawrence, who had previously emailed RFT to defend Vesco-Mock's success in lowering euthanasia rates, an accomplishment that, Lawrence wrote, "should be cause enough for celebration."

At the hearing, though, Vesco-Mock's defense faltered under the grilling from the council. Though she had earned a degree in veterinary science from Ohio State University, at one point she was forced to correct her introduction as "veterinarian," acknowledging that she had actually never been licensed as a veterinarian in either New Mexico or Missouri.

That may have been the least of her issues. According to coverage of the meeting reported by Call Newspapers and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Councilwoman Hazel Erby put the question of racism directly to Vesco-Mock, saying, "We have had complaints that you have made some racist statements, and that concerns me."

This was the first time Vesco-Mock had ever been asked to publicly address the alleged "gangbanging" comment, as well as a related accusation that she had been known to express a preference for "crackers" over black people.

In response, Vesco-Mock's lawyer reportedly whispered something in her ear, and she declined to answer. Instead, she responded to Erby, who is black, saying only that, "I can guarantee you, ma'am, that diversity has never been an issue in my life."

Three weeks later, citing "inappropriate conduct" and "a number of matters relating to the current management of the shelter," Stenger announced he had fired Vesco-Mock.

Stenger didn't release specific reasons for the termination, but he still said enough for staff to recognize the echoes of their complaints to the county's HR department. In a later interview with St. Louis Public Radio, Stenger commented of Vesco-Mock's behavior, saying, "Racist or discriminatory behavior is not going to be tolerated by this administration."

But Vesco-Mock wasn't rattled, and she didn't back down from Stenger. In fact, this wasn't the first time she had come under serious fire: In 2015, prosecutors in Doña Ana County, New Mexico, had charged her with multiple misdemeanors for refusing to hand over a dog's microchip to an animal control officer. In the end, the charges were dropped mid-trial, and Vesco-Mock turned around and sued the Doña Ana County Sheriff's Office for "malicious abuse of process and defamation of character." The sheriff's office settled the case, agreeing to pay Vesco-Mock $90,000.

In St. Louis, things once again shook out in Vesco-Mock's favor. Two months after her termination, her lawyer filed an employment complaint against Stenger, alleging Vesco-Mock was the victim of gender discrimination.

In January 2019, the county announced that it would pay $150,000 to settle the complaint with its fired shelter director. Neither the county nor Vesco-Mock admitted wrongdoing and both agreed not to disparage the other. She agreed never to work for St. Louis County again.

Reached by phone in September, Vesco-Mock's attorney, Edwin C. Ernst, said both he and his client were bound by a confidentiality agreement and could not discuss the shelter. Last year, however, in an interview with St. Louis Public Radio, Ernst did admit that his client had told a group of shelter employees, "Guys, we can't have any gangbanging in the hall here" but he insisted that she had not intended it as a racist statement.

To RFT, Ernst noted that Vesco-Mock has lost much since her firing. "This was her life, she loved working with animals, she got caught up in the whole thing, and unfortunately today she's not able to do that anymore. This was very sad for her, very traumatic for her."

Vesco-Mock still lives in the St. Louis area, Ernst says. She has taken a new job as a corrections officer.

Vesco-Mock may have been traumatized by her firing, but for the shelter employee who had been among the group she called out in the hallway for "gangbanging," the firing was a relief. The shelter, he says, couldn't take any more of Vesco-Mock.

"We didn't put animals down. We held animals for months, almost a year. It was getting too full, and that's when diseases start breaking out," he recalls. "When she left, we were happy. We started to change things back to the way things were. It's taken us a while to get back."

And yet, it also appeared that Vesco-Mock's policies didn't end with her firing. After the dust had settled, Stenger appointed as interim director one of his own policy advisers, Katerina Utz, who had no experience running a shelter. Although Vesco-Mock was gone, employees who protested the ORE policy say their supervisors were still unable to get Utz to shut it down. The ORE policy persisted throughout the rest of 2018 and into 2019, halting only after auditors witnessed people initialing "ORE" on animal intake forms, even though they had no idea what it meant and didn't ask for their animals to be put down.

Not everyone cast Vesco-Mock as the villain of St. Louis County's shelter. Ellen Lawrence, the advisory board member who defended Vesco-Mock before her firing, blames Stenger for the pressure to deliver impressive euthanasia statistics, no matter the cost.

"I felt she really was treated really unfairly," Lawrence says in an interview. She claims that Vesco-Mock had in fact opposed the ORE policy and wanted it stopped but had never been allowed to make organization-wide changes. Lawrence, who serves as an elected councilwoman in Creve Coeur, acknowledges that Vesco-Mock had also brought "a lot of baggage" to the shelter.

"She wasn't a perfect director, which is an incredibly difficult position," she says. "She wasn't given the support she needed."

Even Pamela Hill, the advisory board member who lambasted the shelter's director for the staff's lack of "urgency," says in an interview that Vesco-Mock is miscast as a shelter wrecker. To Hill, the shelter's problems existed long before she arrived from New Mexico as director.

Hill notes that, beyond Vesco-Mock's firing, the details of the damning audit changed little about the way the shelter holds itself accountable, in the sense that it still does not. No one else at the shelter has been fired or disciplined.

"Put the blame where it belongs," Hill says. "The only name people say is, 'Beth did this, Beth did that.' She was in place all of seven months, and we're talking about four-and-a half years of downfall of the shelter. Now, we're being told that these things happened to us because of 'dysfunction,' so no one gets held responsible."

About a year after firing Vesco-Mock, Stenger was also gone. Federal prosecutors who had been tracing political donations to the county executive charged him with three federal felonies, and he quickly pleaded guilty. He's now serving a 46-month sentence in a federal penitentiary in South Dakota.

When the indictment against Stenger was unsealed in April, Vesco-Mock shared a local news story of the case in a public post to her Facebook page. She added only one word of heavily punctuated commentary: "BITTERSWEET!!!!!!!!!!"

During a recent visit to the St. Louis County Pet Adoption Center, the volunteers are out walking the dogs, the routes taking them past the large metallic paw prints that decorate the brick wall leading to the entrance. Inside, the kennels are filled with noisy dogs, most of them pit bulls with names like "Dolph" and "Marco."

A staff member, acting as tour guide, notes that the shelter's adoptable animals — 62 dogs and 40 cats as of October 7 — represent only a fraction of the shelter's current population. She sees goats, pigs, even exotic animals brought in by animal control officers. That's the "control" part of the county's department of Animal Care & Control. As an open-admission municipal shelter, the shelter has to take everything that comes through the front door.

The challenge of meeting both goals, care and control, has stretched the county's patience, and one solution to the problem, privatizing part of the operations, has split the shelter's supporters. But from the perspective of the county, there is a good case to be made for giving up on the government running a shelter.

Spring Schmidt says the time has come for the county to recognize that it's not doing the shelter any good to keep a broken system in place. In an interview at the Department of Public Health's administrative headquarters in Berkley, she says it is true that the advisory board, volunteers and staff all show genuine passion for animals. But they have yet to prove that the shelter can become more than a revolving door for upper management.

"We're caught between the functions the community expects of us [and] the need for credibility from the community to believe that we have the capacity to do it."

It's a bind that's led Schmidt and other county officials to consider privatizing the "care" part of the county's Animal Care & Control. The model would be similar to that of St. Louis City, which in 2019 signed a $694,000 contract with a nonprofit to take over adoption services, though the city kept its own force of animal control officers.

It is likely that a contract to take over the county's adoption services would be even larger. In 2018, the county shelter took in more than 4,000 animals, four times the amount of intake reported by the city. The county's 2019 budget reserved $1.7 million for Animal Care & Control, with most of the funds going to shelter staff and services. Around $350,000 is reserved to pay the salaries of ten animal control officers.

It was the audit that first suggested a new direction for the shelter. A section buried on the audit's second-to-last page featured a list of "other models" for operating municipal shelters, a list that included "All Field Operations Provided by Local Government; All Shelter Operations Provided by Non-Profit."

During the September 19 advisory board meeting, Schmidt announced that the county had begun drafting plans to identify bidders through a formal request for proposal, or RFP. After that, Schmidt estimated, "a good scenario is six months to contract completion," adding that "a nightmare is everything past that."

During the meeting, Schmidt told the board that she expected the Department of Public Health to present its RFP proposal during the county council's September 24 meeting. However, the status of the department's privatization push is suddenly murky. The meeting came and went without action on the shelter. So did the next meeting.

In an October 2 email, Department of Public Health spokeswoman Sara Dayley told RFT, "No RFP has been released currently and DPH does not yet have a timeline for such."

For the shelter staff, however, the impact has already hit home. Some have already taken new jobs in other county departments. If a nonprofit does take over, employees may soon find themselves, at best, forced to reapply to their own jobs, or seek their fortune elsewhere in non-animal care.

Dr. Christine Schultz decided not to wait around to find out. Hired as a veterinarian for the county shelter in late 2018, she tells RFT that she quit in August to take a job with the nonprofit Stray Rescue, "directly because of Spring telling us they were going to privatize."

"I love shelter medicine, and I can certainly deal with the outside frustrations," she says. "But if you're going to tell me you're going to give away my job? Once they started talking about privatization, I knew. If there's any possible way to do it, they will do it as fast possible."

The county shelter has long struggled to maintain a full-time veterinary staff, and Schultz's departure left a patchwork system even patchier, with one part-time vet conducting spay and neuter surgeries, and a second vet signed under an "emergency contract" which makes them available for surgery only a couple times per week.

Doing more with little, though, is nothing new for the county shelter. When Schultz began her duties there in 2018, she says the crowding was so high that on some days she would be required to check on more than 400 animals — which gave her about 80 seconds per animal.

Schultz says the shelter's outreach efforts aren't doing enough to curb overpopulation, but she still bristles when asked about criticism directed at staff by the shelter's advisory board members, especially the critiques aimed at the employee "culture" and lack of "compassion."

"When the population is this high, I know staff members who get to work an hour early," she says. "That's what everybody does there to get things done."

The underlying tensions threaten to strangle the shelter, and Schultz says that while the board and county officials have put thought into an exit plan, they could still do something to fix the situation on the ground — hire a director, improve the outreach, provide job security. Anything.

"That's just what they say at these meetings — that animal control is a blemish," Schultz says, "That's how the Department of Public Health sees it."