For a working jail, major parts of the Workhouse don't work.

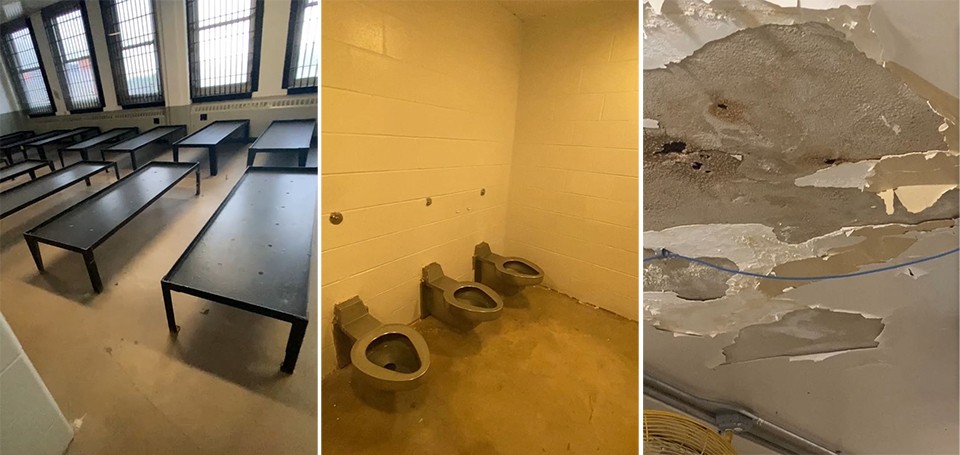

Every time it rains, water leaks through the flat tin roof and pools on the gymnasium floor. In its kitchen, which produces only bread, insects scurry near a wall-sized row of nonfunctioning refrigerators that serve as storage. Entire housing units are empty, leaving the bathrooms and showers to deteriorate in a slime of soap scum, rust and dirt.

Detainees often describe the Workhouse in the most extreme terms. Some call it hell. Officially, St. Louis calls it the Medium Security Institution.

Inhabited parts of the jail are rarely seen by outside eyes.

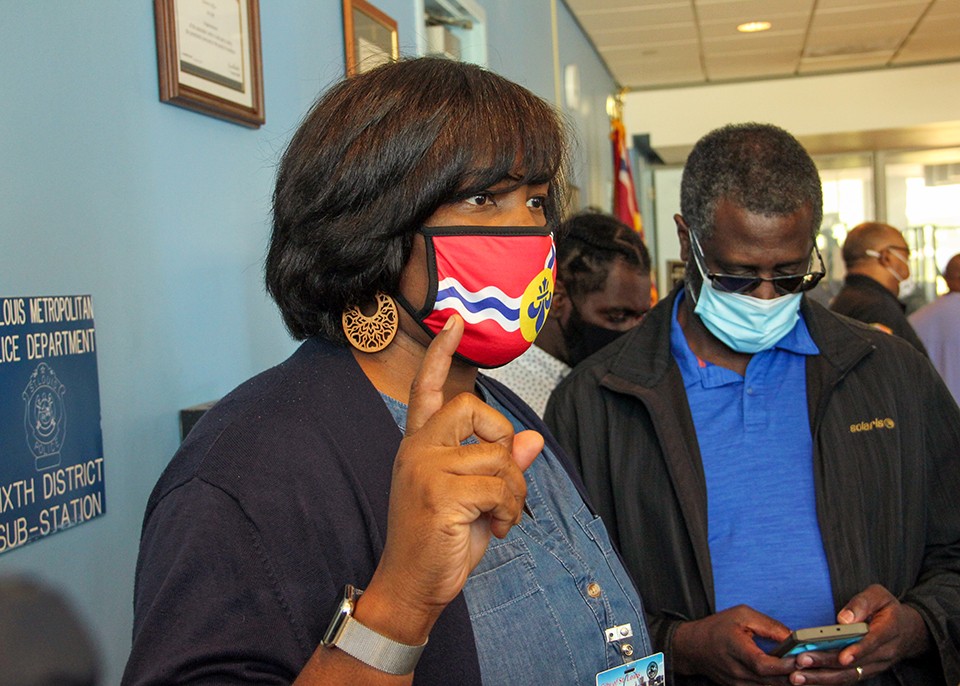

Yet on April 24, St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones and a retinue of some of the most powerful elected officials in St. Louis swept through the 55-year-old facility, conducting inspections and interviews unlike anything seen in the jail's history.

Along with Jones, the tour group included Congresswoman Cori Bush and Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner, the city's top prosecutor. The group toured both of the city's embattled jails that overcast Saturday, starting with the downtown City Justice Center, the site of multiple recent uprisings, and then heading north to the riverfront industrial area, where the Workhouse looms in a pocket of barbed wire facing an auto parts business.

All told, the group spent five hours in the controversial facility, winding their way through its wide white hallways and cluttered medical offices. They listened as a line of five handcuffed detainees in yellow uniforms took turns describing the Workhouse as they knew it, from being sprayed with mace and left in their cells for hours, their skin burning, to being forced to go months without shoes, a condition that makes the freezing nights — which at times are so cold that one man said he could see his own breath — that much more miserable.

At the end of the tour, a press conference waited for Jones outside the aging jail. What she had witnessed that day, she said, had only further convinced her what must be done: The Workhouse has to close.

The visit had left her "very disappointed and shocked and frustrated," she added.

Bush, a former Ferguson protester, was also shaken by what she had seen and heard that day. The inmates had described repeated water shutoffs and meals containing an unidentifiable protein that they nicknamed "rat back." As Bush walked through a housing unit, she said, she could hear detainees chanting after her, "Free the slaves!"

"We didn't just want to complain about what we think is happening, we wanted access to see what's actually happening," Bush told the press, her voice rising in open disgust. "If you had seen the filth, the utter filth, the trash, the bugs ..."

"This is our work," she added firmly. "And now that we are in a position to do something about it, that thing will happen."

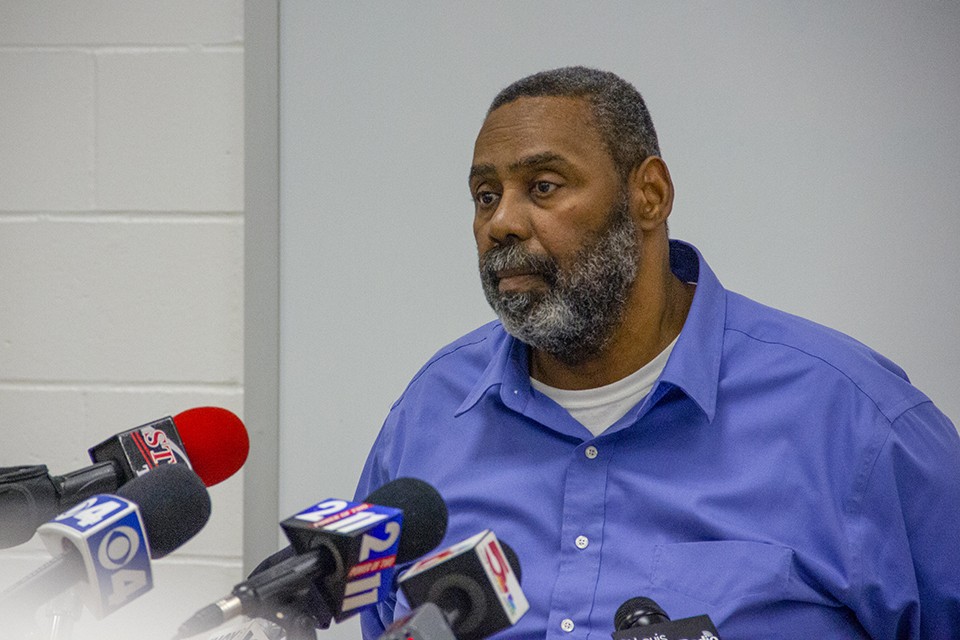

But in the following weeks, a different group latched onto the issue of the Workhouse's conditions — and among them were longtime critics of the campaign to close the facility, including Joe Vaccaro, the chair of the Board of Aldermen's public safety committee. He openly questioned whether Jones and Bush had exaggerated the conditions they claimed to confront that day.

Two weeks later, on a Wednesday morning in May, Vaccaro attempted to stage his own tour of the Workhouse, though with a different aim. Unlike the mayor's group, he invited a TV news crew and reporters to accompany him on what he vowed would be a truly "transparent" tour of the Workhouse.

But Vaccaro's media tour barely got through the front door. Instead, it ran into Heather Taylor.

On April 15, Heather Taylor joined the incoming Jones administration as a senior advisor to the new public safety director. A recently retired St. Louis homicide detective, Taylor had spent years as the president and public face of the Ethical Society of Police, a position that brought her into repeated clashes with the department over its failure to challenge the racism and abuse still thriving in its ranks.

Taylor had less than a month on her new job when on May 12 she confronted Vaccaro's attempted tour at the Workhouse entrance.

By then, Taylor had already spent hours inspecting the facility, including a trip just a few days prior with jail Superintendent Jeffrey Carson.

That visit happened to occur on a day of heavy rainfall, and she saw a very different scene than the visitors might have on the sunny morning of Vaccaro's visit. Carson, who has supervised the jail since 2017, had guided her into the gymnasium to view the pools of water on its floor. He had shown her the largely decommissioned kitchen, where he revealed that the ancient gas-powered ranges were so unsafe that he had ordered them removed. As his explanation continued, Taylor pointed her smartphone's camera at the discolored floor, filming two bugs crawling near a large wooden table where detainees bake bread.

Her experience fit with what Jones, Bush and others had reported from their April 24 trip. But on May 12, their claims about trash, bugs and filth became the impetus for Vaccaro to stage a countertour.

It was the latest example of the city government's complicated relationship with the Workhouse. Last summer, the Board of Aldermen voted unanimously to close the aging facility by the end of 2020 — a deadline that passed as the both city jails struggled to adapt to the pandemic. Although Vaccaro had supported the earlier bill, he and other officials began pushing back as the calls to close the Workhouse heightened during the mayoral campaign season — a contest in which Jones, the eventual winner, promised to close the Workhouse in her first 100 days in office.

Vaccaro had not been invited on the mayor's tour. In an interview with KMOV on May 7, he complained the news of the trip had come as "a total shock."

On May 12, during a scheduled tour of the jail by the Board of Aldermen's Public Safey Committee, Vaccaro tried to shock the mayor back. Along with the committee members, he had invited about a dozen local journalists, including this reporter. Once inside the jail's entrance, the media bunched in the small open space between a security station and the glass doors, waiting for Vaccaro's signal. We watched the alders file through the metal detector and into the waiting area.

But Taylor was waiting for Vaccaro. When he presented the group of journalists from the RFT, KMOV, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, MetroSTL, KMOX and Real STL News — identifying us "as our guests" — Taylor held up a hand.

"They're not coming in," she said.

Over the next fifteen minutes, and with an audience of reporters watching and recording, Vaccaro attempted to negotiate with Taylor. He argued that a media tour was necessary for the sake of transparency. Taylor replied that the rights of the detainees were the city's "first priority," and that while public officials could take photos of what they saw that day, they couldn't film or photograph any detainees.

Taylor repeated herself. There would be no media on the tour.

"At the end of the day," she said, "this is about —"

"This is about transparency," Vaccaro cut in.

Taylor disagreed. "This is about people."

Vaccaro dug in. He didn't believe the mayor's April 24 tour had encountered the conditions decried in the press conference. A fact-finding mission without the media to document the evidence, he argued, would just produce "a whole fake tour about nothing."

Vaccaro brought up complaints sent by former Workhouse residents who had already been transferred to the supposedly more modern downtown Justice Center. There, he said, detainees claimed they were being forced into even worse conditions. "So," he snapped at Taylor, "don't tell me we're doing these people a big favor."

But Taylor didn't budge. "There will be no media here," she said again. "That's the decision, and you can make me the bad guy."

"No," countered Vaccaro, "the mayor will be the bad guy, because the mayor is the one holding out."

He then turned toward the cameras and reporters, a few of whom were live-streaming the debate.

"What are they hiding?" Vaccaro said, now facing his audience. "If the mayor's office is so afraid of what's in this building, why not be transparent? You guys should go ask her. Go to her office. What is she afraid of? What is the mayor afraid of?"

To understand why a media tour would become a showdown at the entrance to a city jail, you have to go back to the summer of 2017, when the conditions in the facility became undeniable — as the truth reached outside the walls through the voices of the detainees themselves.

That July marked the beginning of the activist-led campaign to close the jail, which at the time housed an average of 700 men and women. The protests were sparked by a bystander recording footage of men pleading for help through the jail windows, shouting urgently for relief as the interior temperature rose to more than 110 degrees.

The desperate scene drew national news, and while Mayor Lyda Krewson quickly announced the installation of temporary air-conditioning units, the pressure was on. A lawsuit filed in 2017, alleging "hellish conditions," drew further scrutiny and fueled calls for reform.

So began the recent era of media tours at the Workhouse. The first journey into its walls, however, was a product of some deceit: On August 4, 2017, Alderwoman Megan Green brought two undercover reporters posing as graduate students through the Workhouse — a group that included this reporter and a writer for the St. Louis American. We did not identify ourselves as press.

On that trip, we viewed trash piled in hallways and listened to multiple detainees describe the bugs, mold and misery of their lives. Most had been locked up for more than six months. Some had been there for years. Passing through a pod, a woman whispered at us, "This place is hell."

The undercover visit was followed by sanctioned tours. In March 2018, after months of requests by other news outlets, Krewson opened the facility to several TV, radio and print journalists. (Invites were pointedly not extended to the RFT and the St. Louis American.)

From the outset, the city's top public safety staff, who guided the media tours, used the opportunity to demonstrate that the jail was far from the awful image presented by critics.

That framing showed up in the resulting stories. The Post-Dispatch's coverage began with the observation that "Reporters saw no black mold, rodents or infestations of biting insects" and described the temperature as "a bit cool in some spots, comfortable in others."

TV coverage of the tours was similarly focused on evaluating the jail in light of its upgrades. When the stories included statements from detainees, the claims were paired with on-camera denials from Corrections Commissioner Dale Glass and Public Safety Director Jimmie Edwards.

Although most detainees experienced the Workhouse for long periods of time, the tours compressed the facility into a few minutes of television or a short online story. In Fox 2's report, the takeaways included insights such as that "the Workhouse smelled clean inside" and that "for the most part, inmates appeared as content as one could be in a jail."

At other times, city officials were openly dismissive of the detainees' experiences. In September 2018, Glass led a 30-minute tour for journalist Clark Randall, whose eventual story, published in the Guardian, described Glass' reaction to detainees shouting complaints as they passed by the cells. One man, Randall reported, said he hadn't been able to change clothes in two weeks.

"We've had a lot of tours here recently," Glass responded, "so forgive me that some of the inmates want to entertain."

In news accounts and public statements, the tours of 2018 produced a parallel version of the Workhouse from the "hell" described by current and former detainees — a contrast to the years of alleged abuses that covered everything from gladiator fights to overdoses, infestations to black mold, starvation to suicide.

Notably, the public tours were never held on rainy days, and were often set up with plenty of notice for the jail's staff. As a result, the Workhouse came off in subsequent news reports as rough around the edges but functional, secure and benefiting from millions of dollars spent installing air conditioning and upgrading the jail's electrical wiring, security-camera recording system and showers.

This tactic continued in November 2019, when Krewson announced a glowing report issued after yet another tour of the Workhouse — this time one not involving media, but a grand jury.

"While suffering years of bad press due to poor conditions, the current reality of the Medium Security Institution (MSI) was far different," the report said, as it praised upgrades to the jail's "older, more problematic portions." It pointed out "impressive new sleeping arrangements" and a bakery area "as well-equipped and clean as any commercial kitchen."

There was more to the apparent transformation than just physical upgrades, the grand jury found. While their report acknowledged the Workhouse as "still a place of incarceration," the jurors had been impressed by something more abstract than the smell of a freshly cleaned hallway or "improved shower facilities."

The Workhouse had changed, the report concluded, writing, "It does not convey a 'prison' vibe."

In an interview with the RFT, St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones explains that she planned her April 24 tour with the hope that it would show her the "real" Workhouse, not just its best angles.

"I wanted to see for myself, and I didn't want to give them much time to clean things up before going," she says. "They tried — I could definitely tell that they tried to make it seem like everything was fine while I was there."

But even with hasty cleanup jobs, Jones says it was the detainees she spoke to who gave her "a totally different story." One described his transfer to the Workhouse from the Justice Center after a recent uprising. He was still wearing the same mace-soaked clothes and underwear.

For Jones, it's a question of, "Who's telling the truth here?"

"I'm more likely to believe people who are experiencing it," she says, "than anybody else."

The April 24 tour was more than a public relations stop for the incoming Jones' administration, and she's referenced the event in significant ways through her first month in office. On April 28, for instance, she issued an executive order demanding the Department of Corrections provide "all complaints" from detainees going back to 2017.

The announcement stated: "After personally witnessing unsanitary and inhumane conditions inside both facilities, Mayor Jones spoke with detainees who expressed concerns about the carelessness by which Corrections staff handled their complaints."

Closing the Workhouse by July 1, when the new city budget goes into effect, is a steep challenge. The city is rushing to repair its understaffed and embattled downtown jail, the City Justice Center, whose faulty locks were exposed in a series of uprisings and riots starting in December. Consolidating the city's total jail population of roughly 800 into a single facility will be a tight fit. With the Justice Center currently functioning at only partial capacity, the task will likely require relocating some detainees to outside facilities, at least temporarily.

These outcomes were acknowledged in the same budget that erased the Workhouse's annual funding. Under Jones' budget, the city set aside $1.4 million to pay for overflow housing in other jails.

There are practical upsides to closing the Workhouse, Jones argues: It will allow the employees in the two struggling city jails to combine, resolving the chronic understaffing at the Justice Center that left detainees neglected and staff feeling unsafe. The Justice Center has gotten by with a dangerously low detainee-to-officer ratio, Jones says, adding, "obviously, that creates a situation where our jail staff can be overrun."

Under the mayor's plan, the remaining millions that once funded the Workhouse will go toward aiding those leaving incarceration. That includes $1.3 million to expand reentry programs and to hire social workers and provide access to childcare and mental-health services.

Reducing the overall jail population is the only lasting solution, Jones says. Along with promising to close the Workhouse in her first 100 days — a deadline that falls on July 30 — she's announced potentially significant policy changes to the city's public safety spending, shifting funds from long-unfilled police officer positions to struggling emergency services and expanding programs for crime prevention.

"This isn't just about closing the Workhouse and just letting people out, this is about helping people get back to productive lives," she says. "If people feel like they were treated fairly while in the system, with dignity and respect, and get support after they get out — that's going to reduce recidivism in the long term."

May 12 was more than just the date of Joe Vaccaro's attempted media tour of the Workhouse. That day, the mayor had her own plans.

At the same time that Vaccaro was leading a group of reporters toward the jail's front doors, Jones' office was making headlines with a lengthy statement that had nothing to do with the alderman's demands for transparency and everything to do with the conclusions Jones had drawn from her visit on April 24. Particularly, the press release mentioned the "first-hand accounts from detainees ... of lackluster COVID protocols, inedible food, lack of running water, rodents and cockroaches, as well as a fear of violent retaliation from Corrections staff."

The subject of the press release was the resignation of Dale Glass, whose oversight of the jails, according to Jones, was a "failed leadership" that "left the City with a huge mess to clean up."

It was the end of a nearly decade-long tenure for Glass. He had presided over the 2017 Workhouse heat crisis, the first protests demanding the closure of the jail and, in 2018, the media tours in which he dismissed detainee concerns as mere attempts to "entertain" for the cameras.

That era was over. Glass, the mayor's press release concluded, "was not asked to resign."

Vaccaro was outraged. In a recent interview with the RFT, the alderman argues that Glass was responsible for "tremendous" improvements to the Workhouse; he says the department has evidence that the mayor's jail plans will end badly for everyone — especially the detainees crowded into the newly consolidated Justice Center or relocated miles away from St. Louis.

"We haven't fixed the problems," he says. "And shutting the Workhouse down will do nothing."

The Justice Center, he notes, has already endured multiple uprisings. In February, more than 100 detainees took over a fourth-floor unit, with some using furniture to smash street-facing windows and light small fires that scorched the exterior.

If the Workhouse truly closes later this summer, he predicts, "There is going to be such an uprising from the people who are being moved over to CJC and out of town. They're probably going to break the rest of the windows out."

In Vaccaro's view, Jones is trying to close an invented version of the Workhouse — a decrepit, crumbling and irredeemable jail that he says doesn't actually exist. Based on his own tours inside its walls, he insists the Workhouse is much improved and, in fact, necessary for the well-being of the city's detainees.

It's a notable reversal of roles. For most of the last four years, activists, attorneys and detainees have argued that the glowing reports of a well-functioning Workhouse were blatantly alienated from reality, representing a version carefully constructed by its defenders. Now, with the mayor on the side of the detainees, it's Vaccaro accusing Jones of being disconnected from reality, spinning what he calls "a certain narrative that's not necessarily true."

The swirling accusations also complicate the May 12 visit. Both Vaccaro and Jones dispute the other's account of the tour's origin: Vaccaro claims he notified Jones of his intentions beforehand, only for her office to retract permission in a phone call the night before. Jones tells the RFT she and her staff had "no knowledge of prior approval of his tour" and only learned of his attempt when it appeared on the Board of Aldermen calendar.

"I did talk to her about transparency," Vaccaro maintains, as he describes a phone call Jones says never happened. "I told her, 'I'm going to do this. I'm going to take media.'"

Both sides claim to recognize the real conditions of the Workhouse. But across news reports, media tours and lawsuits, the discourse has often become detached from its subject. In this arena, the experiences of detainees, jail staff and public officials are pitted against one another in a scrum of anecdotes, while the rare media tours attempt to extrapolate short visits into definitive descriptions of what it's like to live there for weeks, months and years.

Two pairs of eyes can look at the Workhouse and see completely different things. One day after Vaccaro's tour, he uploaded several photos from what he described as an "unannounced" tour he took to the Workhouse in 2020, before the pandemic hit.

This was the real Workhouse, he claimed. The one the mayor didn't want the media to see.

Two of Vaccaro's photos show the Workhouse kitchen. Aside from some patches on the floor, the space appears neatly organized and fairly clean. One photo shows a large bread-making table and, in the background, freshly baked loaves stacked on a metal rack. Another shows a large bread oven gleaming in fluorescent light. There are no detainees in Vaccaro's pictures.

It is the same kitchen where, in early May, Heather Taylor filmed insects crawling on the spotted floor, just a few feet from the bread-making table and oven. In fact, the oven is among the only functioning appliances in the kitchen — with its gas ranges deemed unsafe and removed by 2018, today all food must be shipped from the Justice Center. Except for bread.

It's like Vaccaro says: When it comes to the Workhouse, it's all about transparency. But the real question isn't who is being transparent — it's who you believe. And who you don't.

"I just keep going back to, you know, what are they hiding?" Vaccaro says. "There is, obviously, two different stories going on here."