This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center as part of the 63106 Project, a St. Louis-based non-profit racial equity storytelling project.

Beverly Jones can hardly wait to get back to the neighborhood that she knows and loves.

It's a neighborhood that's hard to love and in the time of the pandemic even more difficult.

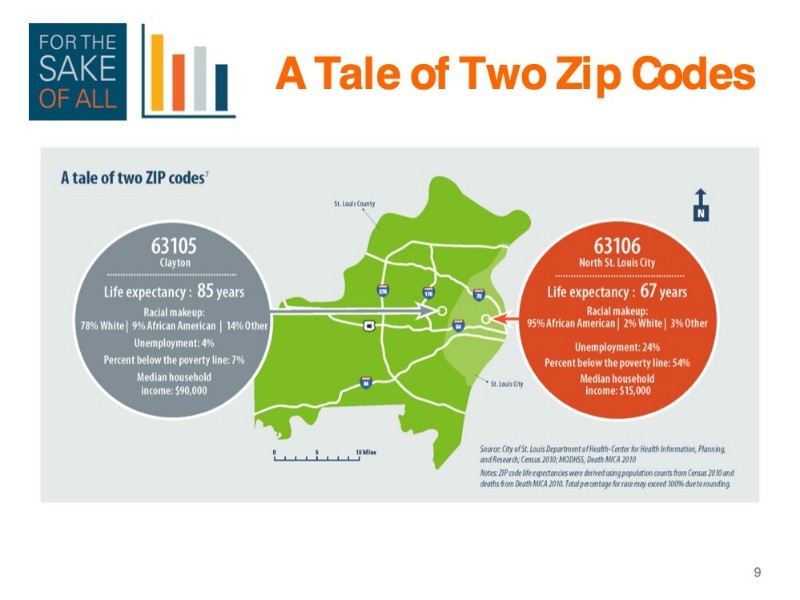

Jones had been a long-time resident of Preservation Square in St. Louis's 63106. The zipcode takes in a couple of square miles north and west of downtown and is home to 12,000 people. 63106 is iconic among social scientists, but not in a good way. It has been identified as having the worst social determinants of health in the region.

A study conducted earlier in this decade through a collaboration involving researchers at Washington University and St. Louis University showed the average life expectancy for a child born in 2010 was 67 years old. That's eighteen years less than the anticipated life span in 63105 — Clayton, the St. Louis County seat, which is made up largely of affluent white families. Of course, this research came before the pandemic and before a crime spike this year that has stricken many neighborhoods in 63106.

Aggravated assaults in 63106 were up 30 percent in the period since COVID-19 arrived, according to an analysis of St. Louis Police crime data.

Jones is 57 years old. She suffers from lupus, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, and perhaps most significantly COPD, a lung disease that makes it hard for Jones to breathe through a mask. So at times she has rolled the wellness dice and simply gone without one. She has other worries as well. Two of her children and a grandchild are in prison where they are vulnerable to COVID-19. And she now has had in her care a grandson, age twelve, and a granddaughter, sixteen, who are struggling with having their mom and older brother in prison. (In all, Jones is mom to four daughters, and grandma to seventeen, plus two great-grandkids.)

"I don't have time to be sick," Jones said when we visited last month, "because I am helping everybody else."

But now she has taken ill. Last week, Jones texted to say she had been feeling poorly and that a test that she took last week revealed that she has been infected with COVID-19. As of this writing she is quarantining. Her granddaughter is with her, and her grandson is living with a cousin for the time being.

The three of them had been living in a safer neighborhood while renovations were underway in Jones's subsidized housing community in Preservation Square, which is managed by McCormack Baron Salazar (MBS). The hiatus might have been a good time for Jones to apply to stay put at the North Sarah Apartments, another MBS complex near the city's trendy and posh Central West End and Grand Center Arts District. There she has a two-story, three-bedroom townhome with access to washers and dryers, a fitness center, computer stations and a community room.

Or she might have considered moving out of the city altogether.

But, no, Jones has been hell-bent on returning to 63106. It's the place where she raised her children, where she came to grips with her drug addiction, then got clean with help from a neighborhood agency, Grace Hill Settlement House. (She celebrated 28 years of sobriety in July). Within 63106 she found work helping others in her community, first as a volunteer, but then slowly working her way into better paying positions at Grace Hill. A supervisor encouraged Jones, a Normandy High School graduate, class of '81, to continue her schooling. So at night she hit the books. She earned an associate's degree in human services and a certificate of proficiency in criminal justice at St. Louis Community College in 2003. She went on to a bachelor's degree at Fontbonne University in 2006, then three years later, earned a master's degree in business management at Fontbonne.

Jones got laid off at Grace Hill in 2012, and her illnesses have limited her, but she has found other ways to serve, working most recently at MERS Goodwill and with Job Corps, a training program for disadvantaged youths.

Jones served full-time for five years with Job Corps and now works there on a part-time basis helping clients with career development.

"She has such a broad background and experiences," says Revelyn Guthrie, residential living manager with Job Corps. Her ability "to get up every day and invest in people is phenomenal."

Jones observes that many social service workers come into her neighborhood with good intentions, but they live elsewhere. They cannot possibly have the insights she has to serve her community. So she feels it's especially important to return, even as many residents are looking for a way out. (Including a neighbor who is also portrayed in this 63106 storytelling project, Kim Daniel.)

Jones is realistic about the challenges in Preservation Square but believes there is a core of great people who will continue to have her back as she has had theirs.

"We take care of each other," Jones says of her neighbors. "If I left town, went on vacation, my neighbors looked out for my place. They made sure my doors were locked. If I had mail being dropped off by the post office or UPS or FedEx, I know my neighbors would take care of my package, and I knew that I would have it when I got home."

Jones started the tenant association at Preservation Square Place in 2016 so that she and other tenants would be kept informed of the changes that were being made at the apartment complex as part of the rehab project. Now she has something more to keep her eye on.

With the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency breaking ground last fall on a $1.7 billion facility on 97 acres in 63106, there's hope the surrounding neighborhood will blossom along with it. But Jones is skeptical about the good intentions of the federal government, the city and redevelopers.

"I've heard so many things about the new NGA site coming and you know it's going to be a different neighborhood" when the facility opens in 2025, Jones says. "But then on the flip side of that coin I've also heard that what they want to do is get rid of a lot of the people who are currently there, and then bring new people in with new development, new housing, new opportunities. But why not for the people who already live there?"