Blake Crews had been one of Ken's success stories. In 2008, a drug charge put him in Meramec's treatment program as a condition of his probation. Coincidentally, he had started a job at Arby's across the street from Ken's office.

Crews wasn't one Ken's immediate clients, but Ken took an interest in his life. For the next five years, Crews worked for the wholesale business Ken owned on the side, functioning as a kind of bodyguard during buying trips to the East Coast and overseas.

On November 2, 2016, Crews and Ken shared a beer on the front porch at the older man's home. But Ken seemed like he was somewhere else. Crews remembers his friend's eyes repeatedly dropping to his phone to check his texts.

By now, Crews knew all about Ken's fixation on Grellner, and so he asked if the texts were new salvos from the cop. Crews remembers Ken responding vaguely — he said people were gossiping about him being gay and a child abuser.

Crews pressed his friend for details and specifics, but Ken never showed him the text messages. Who was feeding him these rumors? Who was he texting? Ken waved the questions off, and the subject was dropped.

Crews planned to return to Ken's house at 7:30 the next morning to help with some furniture he needed to move. "Before I left, he grabbed me on the arm," Crews recalls. "He said, 'Hey Blake, if you show up here tomorrow and I'm gone, or something happened to me, I just want you to know, Jason Grellner did it.'"

Crews laughed it off, though Ken's intensity unnerved him. It wasn't the first time Ken had made such declarations, and sometimes they came as a kind of joke — Ken poking fun at his own paranoia.

The next morning, when Crews knocked on the front door, there was no answer. He went around to the side of the house. Through one of the large windows, Crews glimpsed a lamp overturned on its side, the bare bulb pressed into a couch cushion.

Crews returned to the front door and tried the knob, and it turned, unlocked.

"I open the door and Ken is right in front of me," Crews recalls. "His hands behind his back, beat, tied-up, and just looking straight at me, eyes wide open." Ken had been stripped to his boxers, his chin and lips wet with the blood that pooled around his head. He was dead.

In retrospect, little details in the scene stand out to Crews. The seemingly expert knots and loops in the telephone cords binding Ken's arms and legs, the purple bruises on his neck, the struggle that had knocked down lamps and decorations throughout the room.

"The whole scene was gory. It was evil," Crews says.

He felt for a pulse and started CPR, but the body was already cold and turning blue. Crews couldn't stop thinking about Grellner and Ken's final warning.

After Crews called 911, officers took him into custody as a potential suspect. Crews was never charged. But the next day, while he was in a protective custody cell near the jail's front booking area, he got a glimpse of the three people who were: Timothy Wonish, Whitney Robins and Blake Schindler.

As the three were led down the hallway, Wonish spotted Crews in the cell and shouted a greeting — "Stay strong man! Don't give up! Don't let them turn you!"

Crews remembers being confused. He recognized Wonish and the others because he and Ken had been at their house only a few days before, dropping off groceries. Ken had told him the groceries were meant to sustain the trio while they kicked heroin.

"They were heroin junkies and shitty people," Crews says now. "But I didn't think of them as killers. I didn't think anybody could get that fucked up, to kill somebody like that."

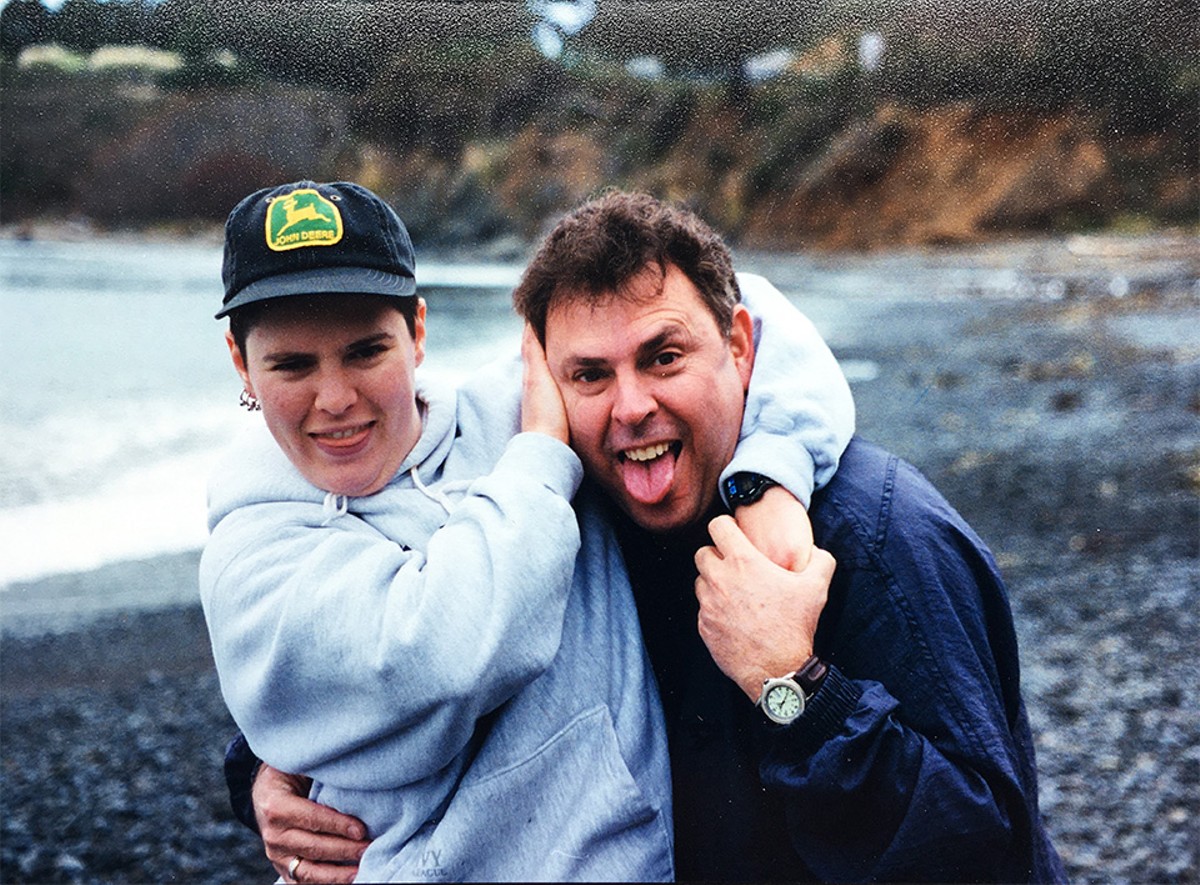

In the aftermath of Ken's death, Kallen began making regular return trips to Franklin County. The house where Ken had died was gutted and sold at a loss. In lieu of a funeral or memorial service, Ken was simply cremated. His remains now reside in a mason jar in Kallen's home. The family has yet to organize a memorial service or formal funeral.

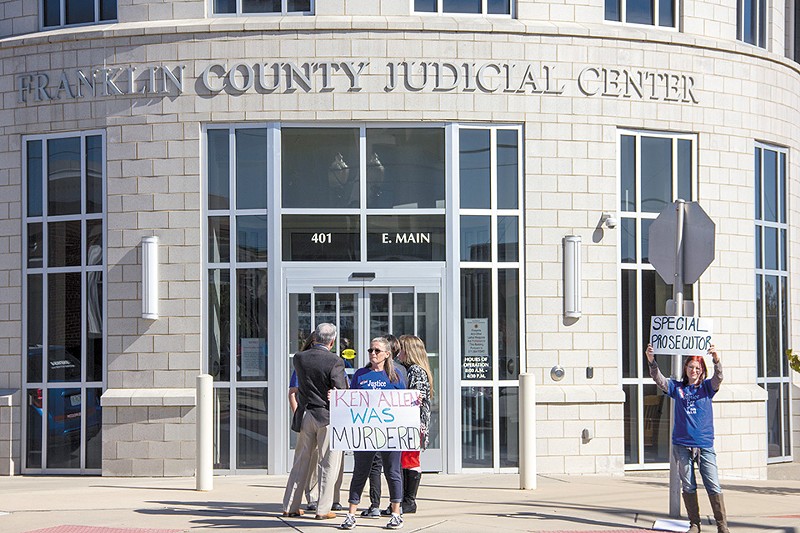

While still mourning, Kallen started emailing the prosecutor's office about the case. But even with suspects in custody, the circumstances of Ken's death didn't add up.

"It didn't make any sense," Kallen recalls thinking at the time.

And like Crews, Kallen couldn't help but wonder about Ken's conspiracy theories and his complaints of harassment. Was it ever more than paranoia? Kallen studied Ken's lawsuit, his allegations against Grellner and the local drug task force. By now, Crews had told the grieving Kallen about Ken's last words to him, and Kallen couldn't help but wonder if there was any truth to them. On the other hand, Kallen had to admit that being tied up and suffocated by a trio of dope fiends seemed like a strange tactic for a police hit squad.

What evidence existed seemed to suggest robbery. Hours after Ken's body was discovered on November 3, 2016, Schindler, Wonish and Robins were located in south St. Louis County with nine of the dead man's credit cards, as well as seven of his checkbooks.

In court documents, a Union Police Department detective noted signs of a struggle at the death scene, and that "multiple pieces of property appeared to be missing."

At the time, Robins, 28, was the only one to offer a statement to police. She was dating Wonish, 30, who at that point had a couple of low-level drug charges on his record. Schindler, who is Robins' half-brother, had just turned seventeen.

In a probable-cause document, Robins told police that she'd helped tie Ken's legs together, and that Schindler and Wonish "had participated in the event."

But in spite of the fact that the suspects left a man dead or dying inside the home, the three were initially charged with felony burglary and receiving stolen items.

(Wonish and Robins did not respond to requests at the jail seeking comment. Schindler's lawyer did not respond to multiple voicemails left at his office.)

To Kallen, the picture seemed to indicate more than just robbery. Ken's death certificate had listed the causes of death as asphyxiation and neck compression. But in a February 2017 phone call, County Prosecutor Robert Parks asserted to Kallen that Ken's death appeared to be accidental. Parks suggested that one of the suspects may have sat on Ken's back during the struggle, inadvertently suffocating him as he lay restrained on his stomach.

Parks' explanation — and the lack of murder charges — rankled Kallen.

"When you come into my house, our house, and you strangle my dad until he is dead, that doesn't sound like involuntary manslaughter," they say.

Kallen's increasing skepticism led to the purchase of a wristwatch with a secret video camera built into the face. And when the Allen family met with Parks before a September 2017 court hearing, Kallen hit the record button.

At the meeting, Parks explains that he expected Wonish and Robins to plead guilty to an updated set of charges, first-degree burglary and involuntary manslaughter. Footage from Kallen's camera shows the prosecutor saying that he is "99 percent sure" Schindler will eventually take a plea deal, "but we got to talk him into going back to jail." Schindler had been allowed to stay on house arrest after a stint in drug treatment earlier that year.

On the day of Ken's murder, Parks tells the family, "these three people were all extremely high on drugs." And the available evidence, the prosecutor insists, doesn't support a murder charge. For one thing, the perpetrators are claiming they had been too high to remember the events of that incident. Parks cautions that it could be difficult to prove the element of intent needed for a felony murder charge.

"[Involuntary manslaughter] more closely fits the physical evidence and the scenario that we have," Parks says.

Kallen asks Parks if he recalls the February phone call in which he had claimed that the suspects hadn't physically strangled or choked their victim, rather that Ken had suffocated "while one of them was sitting on my dad's back or had his knee in his back."

Parks nods. "That's right," he says.

Parks was about to realize that he'd been maneuvered into a corner. The day before, Kallen had spoken with (and recorded) the forensic pathologist who performed Ken's autopsy.

The pathologist, Kallen announces to the room, didn't agree with Parks. "He stated that my dad died from asphyxia from neck compression."

Parks cuts Kallen off, and he snaps, "What's your question? Let me put it this way, I have made the choice and we're going to do this."

Kallen won't have it. "They strangled him," they say.

"They didn't strangle him," the prosecutor shoots back. "They sat on his back. I'm not going to sit here and argue with you."

But Kallen has been waiting for this argument, and begins to pantomime the sort of "wrestling hold" described over the phone by the pathologist. "He died in this position," Kallen urges.

Parks again cuts Kallen off. "I'm not going to argue about this," he repeats.

At this point, Jeff Allen, Ken's brother, shouts at Parks to let Kallen speak, and the outburst quiets the room for a few moments. Breaking the silence, Ken's widow, Janet, asks whether the prosecutor's office had actually tested the suspects for drugs. Was there proof that they were high beyond comprehension at the time of Ken's death?

And finally, the prosecutor breaks.

"Do you want to know the truth?" Parks asks Janet Allen. "The truth was your husband was a pedophile."

The room explodes in a chorus of angry rebuttals. "Bullshit!" Kallen says,

But Parks pushes through. He says Ken was under investigation for more than two years over patterns of abuse. Though Parks doesn't mention Grellner by name, he acknowledges later in the recording that the investigation targeting Ken included the Franklin County Sheriff's narcotics unit, which Grellner commanded.

Parks lays out his claims: Ken had "enticed young men to come to his house for sex and then gave them either drugs or money to buy drugs and then let them come back to his house to shoot up."

And, he says, in November 2016, the three suspects went to Ken's home with more than robbery in mind. According to Parks, Ken had previously "allowed the brother of one of the people to shoot up in his house and overdose, and Ken had taken him to the hospital." Parks claims that Wonish, Schindler and Robins had confronted Ken, "to tell him to leave the brother alone." (That person was apparently Schindler's elder brother, then eighteen.)

Kallen manages to cut into Park's monologue. What did these allegations have to with Ken's death?

"That's why I don't want to try a felony murder," Parks responds, "because then these people are going up on the stand and they're going to trash your dad."

Kallen scoffs. "If they murdered him, they gotta go away for longer."

"Well, they're not," Parks says as the hidden camera records. "They're not."