This summer, the Missouri History Museum opened an exhibit called "The Americans with Disabilities Act: Twenty Years Later." When I visited in the fall, the 1,000-square-foot gallery hosting the installation was eerily quiet.

The exhibit is crammed with information — from an iron lung to a poster defining the proper terminology for discussing disabilities. Relics of a less-politically correct time — a program advertises the "First National Convention of Parents & Friends of the Retarded" — hang on the wall near badges boasting slogans including "Not Dead Yet."

The centerpiece of the exhibit is a large color photo of President George H.W. Bush signing the Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, into law in 1990. The actual pen Bush used receives an honored spot in a glass case.

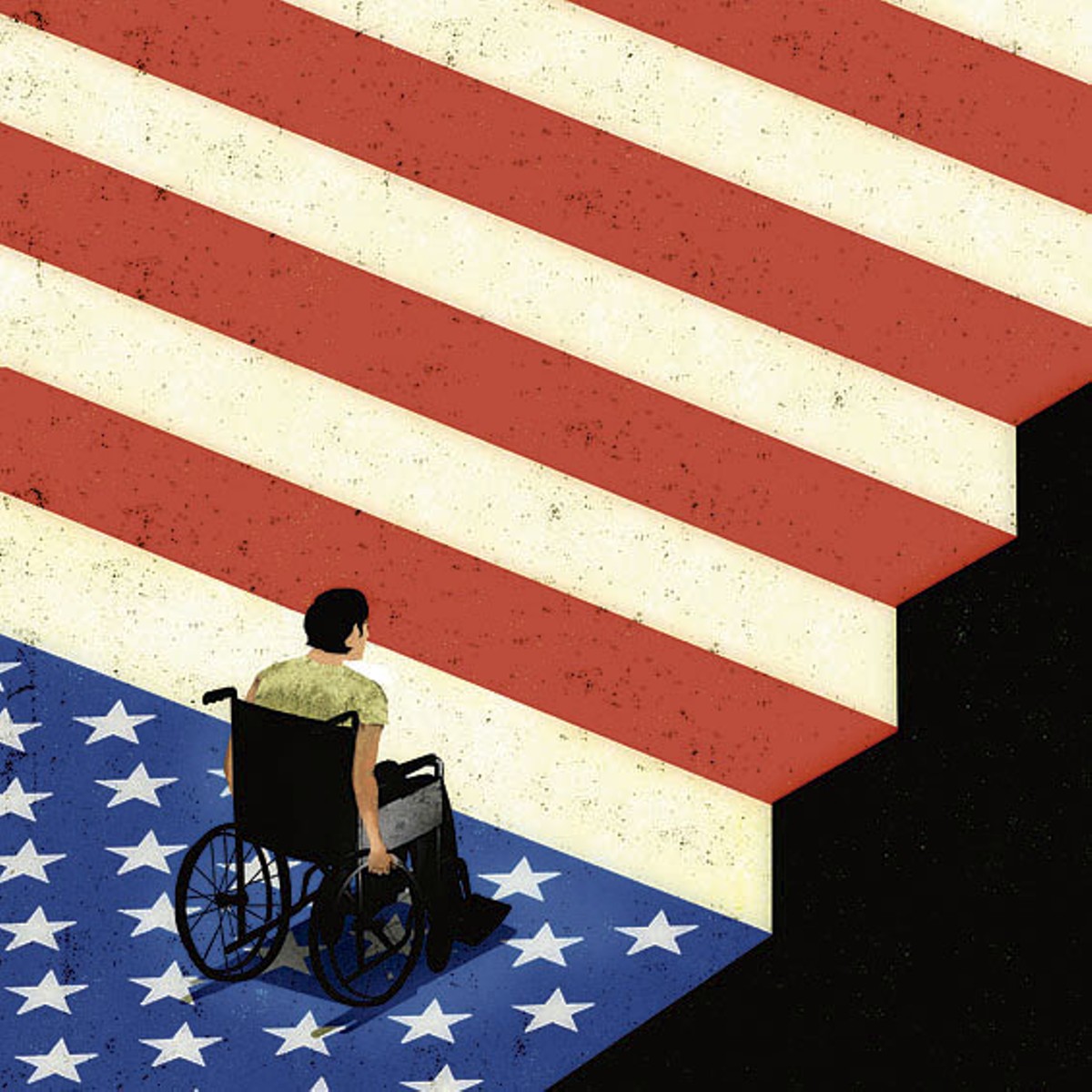

The ADA promises civil rights to Americans with disabilities. It says that public places and spaces can't discriminate against them. Same for private businesses, schools, public transportation and telecommunication services — if they're offering a service to the public, they also need to be accessible to those with disabilities.

Twenty years after the ADA's passage, however, cultural ignorance and condescending attitudes persist. So does discrimination, particularly in the area of health care and building accessibility. And while more people with disabilities have become a part of mainstream society, their unemployment rate is much greater than it is for able-bodied workers.

You only have to look at the history museum's ADA exhibit to see part of the problem. A computer at the entrance invites patrons to leave comments — and plenty have taken advantage of the offer.

A few praise the exhibit; others offer support for the disabled.

Others, well, don't.

"The ADA is one of the most unconstitutional laws ever to be passed," one comment reads. "There is nowhere in Article I, Section 8 that gives Congress the power to force any private business to do anything like this. The law should be nullified by every single State, via the power of the 10th Amendment."

Says another: "Wheelchair lifts on buses cost good money to install, maintain and operate. They also cost riders a good deal of time whenever they are used. My father is disabled, and he has enough courtesy to avoid taking the bus, to avoid inconveniencing others. We have given too little thought to the costs and benefits associated with ADA-type accommodations. Some are clearly win-win; others are more trouble than they are worth."

The negative comments hit close to home: I'm so busy living my daily life, I often forget that I'm a person with a disability. But I am, and that's not going to change. I walk with a pronounced limp, as a result of cerebral palsy. Both of my feet pronate (or roll inward), which means I have to wear shoe orthotics to keep my lower body in alignment. I use a cane when it's icy or snowy, or in large crowds. I use a wheelchair for long distances.

At 31, I live independently, drive a regular car, work full-time and have a loving family, friends and a boyfriend. I sleep late, go to concerts and sometimes drink too much. And I barely remember a time when the ADA didn't have my back. I expect that when I go to the grocery store, I'll be able to find handicapped parking. I count on being able to cross the street using ramps.

But despite these protections — and normalcy of my everyday life — I'm constantly reminded that I am disabled.

A few years ago, I zoned out while shopping at Whole Foods, as I tend to do while grocery shopping. While wandering aimlessly around the cheese counter, a stranger called out to me: "Excuse me, do you have cerebral palsy?" My Zen-like state dissipated, as I said, "Yes?" The woman revealed that she had a relative with cerebral palsy, enthused that she thought it was so great I was out and about and ended the conversation with a pick-me-up somewhere along the lines of, "Keep up the good work!"

While I knew she meant well, the exchange upset me deeply. I wasn't a hero or a special snowflake; I was buying cheese.

This isn't an uncommon occurrence, either: In October, I was flying out of the Las Vegas airport. A worker saw me exit a taxi and immediately greeted me with a wheelchair — a great help to me in airports, because the long distances and crowds can be difficult to navigate. But then she started asking my cab-mates — strangers I just met at the hotel and shared a taxi to the airport with — about my luggage and travel plans, as if I wasn't there. ("Is she checking luggage?" or something to that effect.) I spoke up for myself, but the connotation was that I ceased to be an independent person the second I sat in a wheelchair. In reality, I'm well traveled and frequently fly — most often alone.

For the most part, people mean well. But sometimes, it's hard to give them the benefit of the doubt. When I lived in Boston, cab drivers and neighborhood kids would ask me a variation on the question, "What's wrong with your leg/foot/knee?" — or simply, "What's wrong with you?" A few years ago, after I parked in a handicapped parking space at a Cardinals game, the garage attendant mimicked someone with a limping gait; the insinuation was that I didn't seem as if I would be disabled enough to park in such a spot. Then he saw me walk. (He apologized profusely when I returned to my car after the game.) A friend of mine once caught a stranger at Off Broadway mocking my lurching walk — behind my back, so I didn't see — and gave him a death-stare on my behalf.

I was diagnosed with cerebral palsy (specifically, the type called spastic diplegia) at fifteen months old. Cerebral palsy is a catchall term for a group of disorders that aren't progressive or contagious. In my case, we're not sure why I have it, although CP is common in premature babies, which I was.

As a toddler in Cleveland, Ohio, I had surgeries performed on my heel cords, hamstrings and hip flexors, to help loosen the spasticity in my muscles, which were like taut rubber bands — so tight they prevented me from walking.

I took my first unassisted steps at four years old. I didn't need a walker and didn't need a wheelchair, but in the early '80s, there wasn't really an alternative that fit my abiliities. To help me keep balanced, my physical therapist invented devices that we called "poles" — broomsticks wrapped in colorful stripes of electrical tape that were stabilized by crutch tips. (These colors changed by the season or occasion: brown-and-orange for Cleveland Browns season or white ribbon for my First Communion.)

My disability, while obvious, was mild. I couldn't walk long distances, but I could walk. Going up steps could be difficult, and many gym activities were out of the question — no rope-climbing for me! — but otherwise, I was just a precocious toddler. I attended nursery school and was taught to read. I watched Nickelodeon religiously, adored my Care Bears and Strawberry Shortcake toys and was a total brat to my younger brother.

Then came kindergarten.

When it came time for me to enter kindergarten in fall 1985, the logical next step was my neighborhood public primary school, a five-minute ride from my house. Although this was pre-ADA, it was after 1975's Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which required public schools to educate disabled children in the least restrictive environment.

Things weren't so simple, however: The neighborhood school had never had a physically disabled student attend classes there. In the past, students with disabilities who resided in my district — regardless of whether their disability was physical or cognitive — were bused to a separate school outside the neighborhood.

Before the ADA, segregating people with disabilities made it "much easier for people to solve the issues of disability," says Colleen Starkloff, cofounder of the St. Louis-based Starkloff Disability Institute. "Because then you can put all the disabled people in one place and take care of 'em. The problem with that is that you don't see people with disabilities as your equal; you see them as a group that needs to be cared for."

My story took a different turn. After visiting the school to which I would be bused, my parents didn't feel it was the best place for me. I was tested, to make sure my cognitive development was still progressing normally. After the district realized that the modifications I needed would be minor — such as, I required help on and off the school bus and extra time walking around — they accepted me into the neighborhood school.

I was lucky — I had stubborn parents for advocates and good test scores on my side. For many disabled students, access to education wasn't always a given in those pre-ADA days. (Even today, many parents will tell you the educational opportunities for disabled students are still far from ideal.)

David Newburger, a lawyer who's also the Commissioner on the Disabled at the City of St. Louis, had a very different experience when he started school in the '50s.

He contracted polio in 1944 as an infant and now uses power-assisted wheels. In first grade, he was sent to a so-called "crippled children's school," he recalls.

It wasn't much of an education. "I wasn't learning to read," he says today. "They were babysitting, which is what I think special school often does today."

Newburger's parents eventually moved closer to a one-story school. "And I had a third-grade teacher who realized I wasn't reading and taught me to read," he says.

"And if I hadn't run into her, I wouldn't have ever been a lawyer, much less everything else I do."

By the time I was about to enter fifth grade, my parents weren't the only ones challenging the status quo for people with disabilities: Congress passed the ADA right before I turned eleven years old.

Back then, the legislation wasn't on my radar. I was too busy listening to sports-talk radio, discovering boys and reading voraciously to realize it existed — much less that it would have great significance in my life.

The ADA inspired vehement responses, however. "When the law came out, law firms went into the business of consulting with companies on how to avoid the ADA," says Max Starkloff.

Starkloff, who became disabled at 21 after a car accident, cofounded the nonprofit disability advocacy organization Paraquad with his wife, Colleen, in 1970. (They've since left the organization to found the nonprofit Starkloff Disability Institute.) Now 73, he uses a power wheelchair and is on a ventilator.

He remembers maneuvering in public in the time before the ADA. "Getting off a curb, you had to go look for driveways," he says. "And if you look for driveways, you're looking for cars. You're dodging cars in the streets to get across the street. And transportation — you borrowed people's vans or you found other ways to deal with it. Or you didn't go anywhere."

The ADA sought to change that. And in St. Louis, the results have been tangible — things such as curb cuts, ramps into buildings or handicapped parking spaces are common here thanks to the federal legislation.

"It's just [been] a very gradual but steady increase in overall accessibility," says Gina Hilberry, president of Cohen Hilberry Architects, a firm that consults on ADA compliance. "The ADA was enacted twenty years ago, and for a while it seemed to have a very slow start. But it just seems to, year by year, pick up ground and impact."

Although the ADA doesn't enumerate specific accommodations — the law doesn't dictate exactly what a place must do to become accessible — for Hilberry, its tangible effects are also symbolic.

"Go around the city and see how many places there are curb ramps," she says. "Occasionally, they still aren't installed. But everywhere there is a curb ramp, there used to be a six-inch step. And that six-inch step is equivalent to a barrier saying, 'You're not welcome here.' Every single street corner you can think of, there's now an open door where there used to be a closed door."

That's not to say that things are now perfect — or that the ADA solved everything. In fact, Congress found that the law's language was not being interpreted the way it intended. This spurred the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, which condemned (and aimed to banish) the overly strict definition of "disability" which prevented many Americans from being protected.

The amendments highlighted an ongoing problem with ADA compliance: Disability is an individualized thing. What accommodates one person isn't appropriate for another person; everybody's version of his or her disability is different. (Anticipating what's appropriate is also tricky: While portions of the Missouri History Museum's ADA exhibit are written in Braille, the exhibit doesn't have an MP3 player with audio commentary, which might be best for some patrons.) But sweeping legislation isn't necessarily tailored to individual needs — and doesn't take unique situations into account.

Also, the ADA is complaint-driven — enforcement only happens when someone speaks up. Today, every branch of the Saint Louis Bread Co. is ADA-compliant. But that's only because in 1994, the Central West End location, which was then on Maryland Avenue, was sued because it wasn't wheelchair-accessible. Two years after that, in response to another lawsuit, the federal government ruled that the Saint Louis Zoo needed to make its trains accessible. (David Newburger represented the plaintiffs in both cases.)

Still, a settlement or accessibility agreement can be reached without litigation — and in many cases, I've found that having a conversation about potential violations can be effective. For example, I went shopping at a local grocery store a few years ago — and they had picnic tables placed in the handicapped parking spot. After speaking with store management, the tables were removed.

But it can be difficult to figure out where to complain. Many disabled people rely on Metro transit services. Yet if you Google "MetroLink" and "ADA," you're directed to file your complaint with an e-mail address that, apparently, no one checks. My attempts to communicate with that agency were ignored for nearly a month — until RFT contacted the press office. At that point, I received immediate service. How many disabled people aren't so lucky?

And there are plenty of super-technical loopholes and exceptions. Say you're opening a new restaurant on the site of a preexisting restaurant that wasn't ADA compliant. Because it doesn't involve construction, some municipalities do not have jurisdiction under their building code to force ADA-related changes, Newburger explains.

That doesn't mean skirting compliance is legal; the new restaurant is still liable for any violations should a private citizen raise the issue. But complaining to city hall in most cases would do no good.

Confused yet? You're not the only one. One of the roadblocks to ADA accessibility, says Gina Hilberry, is "simply people's understanding of what the law is and how it applies under what circumstances."

Besides that, issues of physical accessibility are often thwarted by negative attitudes and a lack of foresight. Hilberry says that accessibility "tends to be one of the last things on the plate" for architects.

Newburger sees things improving. For instance, fifteen years ago, he says, "We had a litigation against the public-housing authority, because they were designing federally funded housing that just didn't comply."

He recently ran into the architect on the other side of that litigation — at a seminar about the design revisions to the ADA going into effect in March 2011.

"We had a brief chat, and he said, 'You taught me so much I didn't know,'" Newburger says.

The public school district I attended was one of the best in the Cleveland area. The education I received from kindergarten through my high school graduation was appropriate and challenging, and it prepared me for college. I was lucky enough to get into Harvard University and chose to enroll, in no small part because their disability services and accommodations fit my needs. Without my parents' efforts to place me in mainstream schools, it's doubtful I would have ever made it that far.

Besides providing a proper education to students with disabilities, mainstreaming them serves another important role: It creates visibility.

Pre-ADA, students may not have been exposed to any classmates with disabilities. Today, that's changed — and that's a good thing for everyone.

"If you put all disabled kids into a school for disabled kids, then the kids don't learn about the real world," says Colleen Starkloff. "They only learn about themselves and each other. But they don't even learn to socialize or assimilate or integrate with non-disabled society. But the real world is much bigger than people with disabilities. And the best way to live a life with dignity and full equality is to live with everybody else and do what everybody else does — and that is, go to work, go to school, have a family, be part of the society."

During college, I was an intern at Alternative Press magazine in Cleveland, which introduced me to the (not as glamorous as you think) world of music journalism. After college graduation, I spent three years in Boston freelancing and placed articles in the Los Angeles Times, Salon.com, Amazon.com and Billboard. It was my freelance work for papers such as Cleveland Scene and the Kansas City Pitch that put me on RFT's radar, however — and in June 2005, I took the music editor position here.

I didn't grow up thinking that my disability limited me, either professionally or socially. Part of this was because of my upbringing. My parents never coddled me or treated me like I was fragile; I was their daughter, not their disabled daughter. But I think my mindset also stemmed from being immersed in mainstream schools and society. And there was no question I had every right to be there — with the passage of the ADA, people with disabilities had the right to fully participate in society. Gradually, seeing someone using a wheelchair, walking with a cane or using a Seeing Eye dog wasn't something extraordinary.

Max and Colleen Starkloff, who have been married for more than three decades, laugh about an experience they had while Christmas shopping in 1973. So they could buy gifts for each other in secret, the couple separated for an hour — and in parting, Colleen gave Max a kiss.

A woman passing by saw the gesture, and she was so surprised that she ran right into a jewelry counter.

"I mean, she just walked right into it!" Colleen recalls. "The reason was — she was staring at us. She hadn't seen anybody kiss somebody with a significant disability like Max. He was in a power [wheel]chair, he was very handsome, and I kissed him.

"But that was so odd to this lady — it was such an anomaly — that she got distracted, and she walked right into that jewelry case and fell over it. And I said to Max, 'What's up with that?' And he goes, 'Sweetie, people don't see this.' And in fact, if you looked around at that time, we were an anomaly — you would not go into a mall or into a grocery store or any dense public setting and see people with obvious disabilities. Now you will. But you didn't back then."

As people with disabilities have become more visible, that doesn't mean society always accepts them with grace. Strangers have stared at me my entire life. As a little kid, this bothered me so much that my mother told me I should tell them, "Why don't you take a picture? It'll last longer." (So I did, although I discovered that a glare was just as effective.) Little kids still do their best impression of the girl from The Exorcist when they see me walk.

A note included in the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 acknowledged the continuing bias: "In enacting the ADA, Congress recognized that physical and mental disabilities in no way diminish a person's right to fully participate in all aspects of society but that people with physical or mental disabilities are frequently precluded from doing so because of prejudice, antiquated attitudes or the failure to remove societal and institutional barriers."

Colleen Starkloff knows that all too well.

"If you had asked Max and me 40 years ago, when we got into this field, what was the single most significant issue facing people with disabilities, we'd have told you negative attitudes toward disability," she says. "And if you ask us today, what is the single most significant issue facing people with disabilities? We're going to tell you it's negative attitudes toward people with disabilities. It hasn't changed."

Joan Lipkin cofounded the DisAbility Project, a local theater group that increases disability awareness through performing original plays. Its members have a range of disabilities, and so the accessibility of every aspect of a performance space is an important consideration.

Lipkin recalls visiting a school where the troupe was to do a show and finding that the bathrooms weren't accessible.

"The person at the school, the very well-intentioned teacher who was also involved with diversity issues, she so wanted us to come in," Lipkin recalls. "So she said, 'Can't people go before they leave the house?' and I said, 'Oh sure they can, but you know how nature is, one never knows about things.' She said, 'Well, can't they just go, you know, into a corner and, like, use a bottle or something?' We've had many of those kinds of conversations."

The fact that decades of discussion are finally leading to change is a great thing. But it's disheartening that so many misconceptions still flourish.

Lipkin theorizes that our culture's fear is often what holds us back.

"We need to tap into the awareness that we are all vulnerable, that in the blink of an eye any one of us can be faced with the reality of disability of one kind or another," Lipkin says. "I think that this vulnerability may be the basis of some of the pervasive psychological, social, societal resistance to dealing with disability, because people don't want to recognize their [own] vulnerability."

Lipkin quotes a disability activist named Paul Longmore: "He said... 'We harbor unspoken anxieties about the possibility of disablement, to us or someone close to us. What we fear, we often stigmatize and shun — and sometimes seek to destroy.'"

The danger in resisting that vulnerability — and giving in to the fear — is that disability isn't an isolated occurrence. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 12 percent of the U.S. population has a disability. Colleen Starkloff points out that, as the millions of baby boomers age, they too will face the prospect of developing a disability.

"Even though boomers don't necessarily identify with disability — because there's a stigma attached to being disabled — they're going to become disabled because they can't see, they can't hear, they can't walk or they may lose some of their mental capacity," she says. "Whether they want to call it disability or not, those are disabilities. And if our society doesn't become more reflective of how to include them, and enable them to age in place successfully and happily, we've got a big problem coming."

Perhaps more than most people, I worry about aging in the future. Although cerebral palsy itself isn't progressive, the physical manifestations of the disorder are affecting my body. Every time I see my specialist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, she tells me that my joints are going to wear out faster than regular people's, because of the wear and tear my gait puts on them. When? Not until I'm in my 50s, she tells me. Still, on days when my knees ache so it hurts to stand up, or my back and feet throb with pain, I fear that the aging process has already started. There's very little research available on aging of those with cerebral palsy — so I often feel as though my future is a blank slate. And so I wonder what my life will be like in the future, what will happen if I'm in too much pain to walk or work.

So far, I've been very lucky in terms of employment. As a music critic, any accommodations I need to do my job are basic: a chair, because standing for long periods of time is difficult for me, and close parking. St. Louis concert venues have always been extremely flexible, and I've never had any problems.

Other places haven't been so welcoming, however. At a multi-level venue in Chicago, a worker viewed me with suspicion and skepticism when I asked to use the elevator, as if I didn't really need it. And when I attended South by Southwest in Austin, trying to find a seat at many venues was fruitless: Owing to what I was told was a directive from the fire marshal, venues couldn't have extra furniture such as chairs around. At one club, workers asked me to give up the chair in which I was sitting; citing my disability, I refused, and I was allowed to keep it. On another occasion, though, the venue made me relinquish my chair and stand. I ended up having to leave that show early, because I couldn't physically handle being on my feet anymore.

Many people I interviewed for this story cited unemployment as the biggest current problem facing people with disabilities. According to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics figures for October 2010, the overall unemployment rate for people ages sixteen and over who had a disability was 14.8 percent. (The rate for those without a disability was 8.8 percent.) More troubling, only 21.4 percent of people with disabilities were participating in the work force — compared to 69.8 percent of people without disabilities.

The very first title of the ADA addresses employment discrimination and ostensibly offers protections. Still, according to Tom Kennedy, a Clayton-based lawyer, lawsuits involving employment and the ADA are becoming increasingly difficult to win.

"The employment problem is, either you're not disabled enough to be qualified, or you're too disabled, and therefore you require too much accommodation — and it costs too much and so forth," he says. "In the employment area, frankly, it's so difficult to do an ADA case. I can't figure out a way to do an ADA case and succeed."

In David Newburger's eyes, battling employment discrimination also involves a shift in mindset.

A person with rheumatoid arthritis, he says, may need four or five hours before they're functional in the morning, so they can't necessarily start by 8 a.m. They might have to start their workday later — and therefore work later. But even though they can still put in an eight-hour day, some judges have ruled that their place of employment doesn't necessarily have to accommodate them.

That's not what the ADA intended.

"The ADA says, 'Wait a minute — people with disabilities do things all different ways, but if they're productive, if they produce the same thing as the guy who comes in from eight to five, then it doesn't make any difference,'" Newburger says.

"It's this cultural thing that we need to get people to realize, 'It's OK to come in at 9:30 and still be a productive employee.' Once we get that through, the ADA will be much better at employing people with disabilities."

Over the summer, I requested to pre-board a Southwest Airlines flight. I typically need extra time to board because I walk slower, and the downward-sloping jetway throws me off balance. (This is exacerbated by the fact that I'm usually carrying a backpack with my laptop.) I made my request while I was sitting in a wheelchair, as my boyfriend had pushed me down the airport concourse. I told a Southwest employee that I could walk on the plane — I just needed some extra time.

She denied my request.

This was surprising to me for many reasons. Besides the fact that guidelines from the federal government state that carriers "must offer an opportunity for pre-boarding to passengers with a disability who self-identify at the gate as needing additional time or assistance to board," I've pre-boarded Southwest flights dozens of times — and have never been questioned or denied.

After I filed a complaint, the airline got back to me and noted a recent policy change. Because I can walk on the plane unassisted and don't need a specific seat accommodation, I'm only allowed to board before "family boarding," which takes place between the first two boarding groups.

While in theory this makes sense, in practice, it's not a safe alternative for me. On Southwest flights, regular boarding tends to become rushed, which means that it's likely family boarding will begin as I'm still walking down the jetway. Having little kids underfoot, or harried passengers pushing past me, is a recipe for a spill — I've fallen before because I was walking too fast toward the plane. It's important that I walk slowly, so I don't hurt myself. (Besides that, family boarding doesn't always happen, because not all flights contain families.)

In essence, I'm being punished for not being disabled enough to require extensive accommodations. And that's infuriating. I don't want to be wheeled onto a plane. I want to walk on just like everyone else does.

Yet, compared to other travelers, I'm actually lucky: In October, a Michigan man named Johnnie Tuitel, who has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair, was told by US Airways employees that he was "too disabled to fly" by himself — and was removed from a flight.

I've never been the type of person who considers leaving my house to be a political statement, never considered myself to be changing attitudes or raising awareness by just living my life. But I was surprised to be overwhelmed with sadness as I finished going through the exhibit at the Missouri History Museum. In fact, the exhibit was more powerful to me than I thought it would be.

Until I started reporting this story, I had never really considered disability rights to be a civil-rights issue. Perhaps because I don't remember living in a world without the ADA — or perhaps because I've always functioned in the able-bodied world — the idea that I would be denied rights and access because of how I walk never occurred to me. I often forget that I have a disability. But I was reminded that to others, I'm nothing but my disability.

Indeed, the exhibit hit home for me that discrimination was perfectly legal up until twenty years ago. Only twenty years ago — a drop in the bucket, time-wise — someone like me didn't necessarily have the same rights as other people. Just a short time ago, I was considered a second-class citizen, someone not necessarily deserving of the same rights and privileges other people take for granted — being able to enter a building, restaurant or a hotel; having a job; making a phone call; crossing the street safely.

The comments left by attendees perpetuated so many self-defeating disability myths — that those with a disability are a burden, they cost businesses money, that the ADA is unconstitutional. That last comment made me angry: The idea that my right to equal access can be reduced to a political talking point — and, in fact, something that isn't even a right at all, because it allegedly conflicts with American freedoms — shows a shocking lack of compassion. Anyone who would say the same thing about a specific ethnic group would be labeled a racist or a bigot.

Why is it acceptable to think that those with disabilities don't deserve protection for basic human rights?