No theater company in town delights more in transporting its audiences to remote places than does Upstream Theater. For its current offering, Conversations with an Executioner, we are removed to a dingy dungeon in post-World War II Warsaw. Outside the prison walls we hear freedom in the melodic notes of "Lili Marleen," wistfully played on an accordion by Isaac Lifits. Inside, the claustrophobic scenic design by Scott C. Neale does not merely resemble a prison cell; we viewers find ourselves virtually incarcerated. By the time you take your seat (many of which are in the cell itself), the Kranzberg Arts Center might as well be a continent away.

The executioner in the play's title is SS police general Jürgen Stroop, a protégé of Nazi chieftan Heinrich Himmler and the architect of the 1943 destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, where more than 56,000 Jews were exterminated. In March 1949 Stroop was himself waiting to be executed when a Polish freedom fighter named Kazimierz Moczarski (who had been arrested by the newly empowered Communists) was placed in the same cell with the mass murderer. Initially Stroop was suspicious that the new arrival might be a government plant. But after he became convinced that Moczarski was a bona fide inmate, for several months the general bragged about his splendid military career and his reverence for Himmler and Hitler, "the two great men of twentieth-century Germany."

In time, Stroop was hanged on a prison gallows and Moczarski was freed. His account of his eight months with Stroop was published posthumously in 1977. Upstream artistic director Philip Boehm has adapted Moczarski's memoir into a 75-minute theater piece. Though the subject matter is compelling, a stage adaptation poses daunting challenges.

For starters, who are the characters? The memoir provides a detailed portrait of Stroop — austere, vain, verbose — but who is Moczarski? Because he barely exists in his own book, his personality needs to be created. Then there is the third cellmate, Gustaw Schilke, a professional soldier from Hanover. Schilke is almost marginal to this story, but if he is to be retained, how can he be used to enhance the story? Finally, the most pressing problem of all: How is a narrative that is mostly talk made theatrical?

In discussing the celebrated taxi scene between Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) and his brother Charley (Rod Steiger) in On the Waterfront, director Elia Kazan once said, "What's good is that they can't get away from each other. If you can get a 'no exit' sign on a scene, if the characters have to confront each other, you've probably got a good scene." Conversations with an Executioner is essentially a "no exit" play. The space is confined, and nobody's going anywhere. Yet there is precious little tension onstage, and the confrontations feel contrived — perhaps because according to the memoir, Moczarski went out of his way to keep his personal feelings hidden in order to keep Stroop talking.

What we're left with is a play about banality — not the banality of evil, but of words. When Stroop finally describes "the Grand Operation" (i.e., the systematic destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto), the account is unmoving. Casualty figures don't automatically make for engrossing theater. Perhaps the most striking aspect of the memoir is Stroop's steadfast lack of remorse. He expresses not one iota of doubt about the rightness of his demonic actions. This insight into Stroop is unclear in Boehm's adaptation (which he also directs).

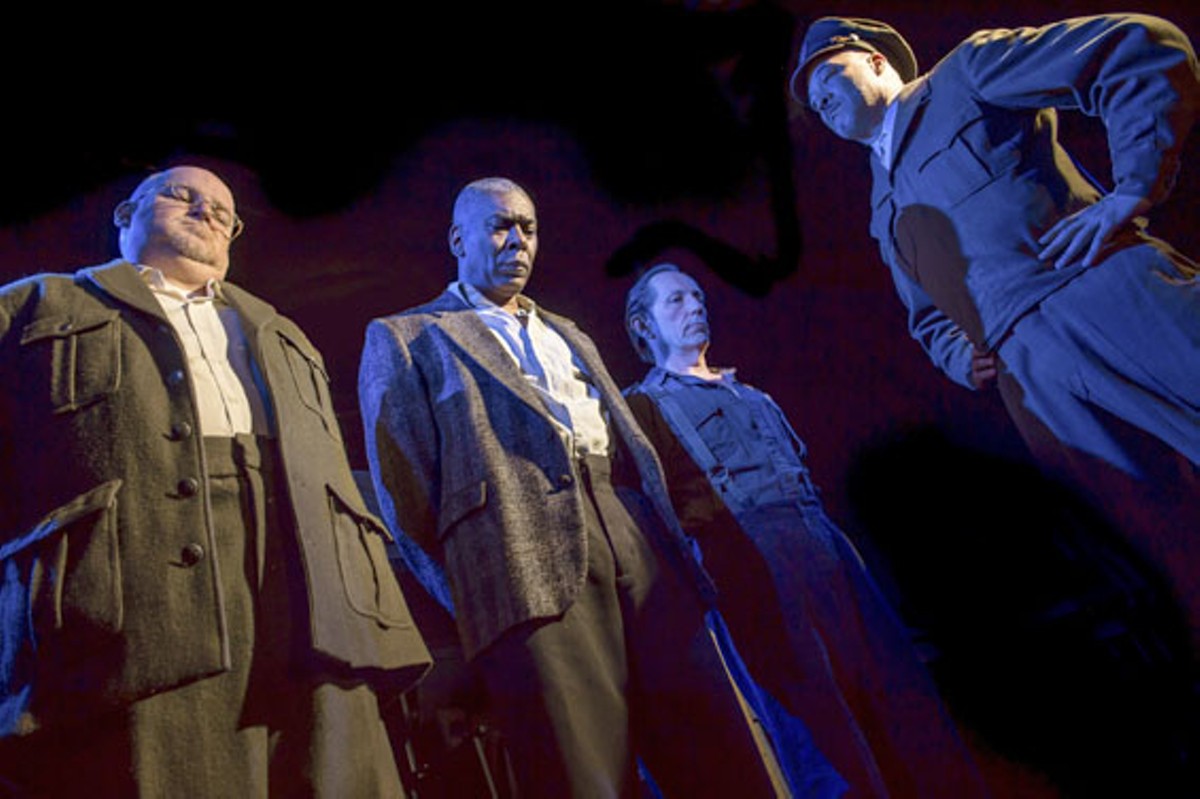

All three principals — Gary Wayne Barker as Stroop, John Bratkowski as Schilke and J. Samuel Davis as Moczarski — have shown themselves to be gifted actors. But in this piece, they're like rock climbers with no handholds to cling to. If Conversations with an Executioner is a misfire, it's an honorable endeavor. But those who would make theater of history should remember that at its most basic, history is personality. History permeates this squalid Warsaw dungeon cell, but the personalities remain at large.