Just after midnight on January 15, 2010, a phone rang inside Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. The caller said in a soft voice that a black male passenger named "Dorian" was "possibly going to be carrying explosives" onto Continental flight 5938 to Washington, D.C.

Police officer Michael Helldoerfer pressed the man on the other end for his name and contact info, to no avail. The flight was scheduled to leave in seven hours.

"This is a pretty serious thing you're calling in," Helldoerfer said. "We need to have some information.... What do you suspect is going to happen?"

The caller hung up.

Helldoerfer notified two sergeants and a lieutenant in his own department. Employees of the airport, fire department, Continental Airlines, the TSA and the FBI — about 100 people in all — were put on notice.

In the frigid darkness, Continental taxied the plane away from the terminal and onto a remote strip of runway. At 5:30 a.m. a K-9 unit arrived. "Lexie," a Belgian malinois, sniffed the plane. She found nothing.

Meanwhile, travelers were filtering into Lambert for early flights. Police tracked down a passenger named Doran Corbin, who was about to board an aircraft to Chicago. But he wasn't their suspect; he was an airman in the New Jersey National Guard.

At last Continental found no reason to detain the plane and cleared it for departure at 7:30 a.m. The plane roared away from St. Louis without incident.

But the matter wasn't over.

Investigators soon traced the threatening call back to a cell phone. Neither its supposed owner, "Alex Devoure," nor the address, a P.O. box in California, actually existed.

So they subpoenaed the phone log from Sprint. The record showed that the cell user had recently called Mid America Arms gun dealership in Affton. When detectives questioned the dealer, he noted that a man named "Dorian" had just inquired about a new paint job for the scope on his high-powered rifle.

Law enforcers then focused on a second detail from the call log. The cell user had often dialed the home of a Denise Williams in the Beverly Hills neighborhood of north county.

Before probing further, investigators presented their findings to assistant U.S. attorney Howard Marcus on March 1. As they talked, two names in the case struck Marcus. A decade earlier, he'd prosecuted a guy named Dorian Williams.

A check of court documents showed that 34-year-old Dorian Williams had an extensive criminal history. The files also revealed his strange interactions with Big Shark Bicycle Company in the Delmar Loop and an unusual interest in track cycling.

On March 17, 2010, an airport detective phoned Williams, hoping to trick the suspect into revealing more information. Williams answered by name.

"Hi, Dorian," the detective said, "I'm with the Missouri Bicycle Racing Association."

"I don't think so, homeboy," Williams said, and hung up.

Undeterred, investigators drove out to Denise Williams' residence in the early morning of March 25. They parked on a side street. As they walked toward the house, they glimpsed someone in the doorway matching Dorian's description. But the figure vanished.

When his mother, Denise Williams, consented to a full search of the house, they couldn't find the suspect. They asked Denise, a night nurse at St. Louis Psychiatric Rehabilitation Center, where her son might be.

"He comes and goes," she told them.

She wasn't fibbing. He'd been coming and going for years.

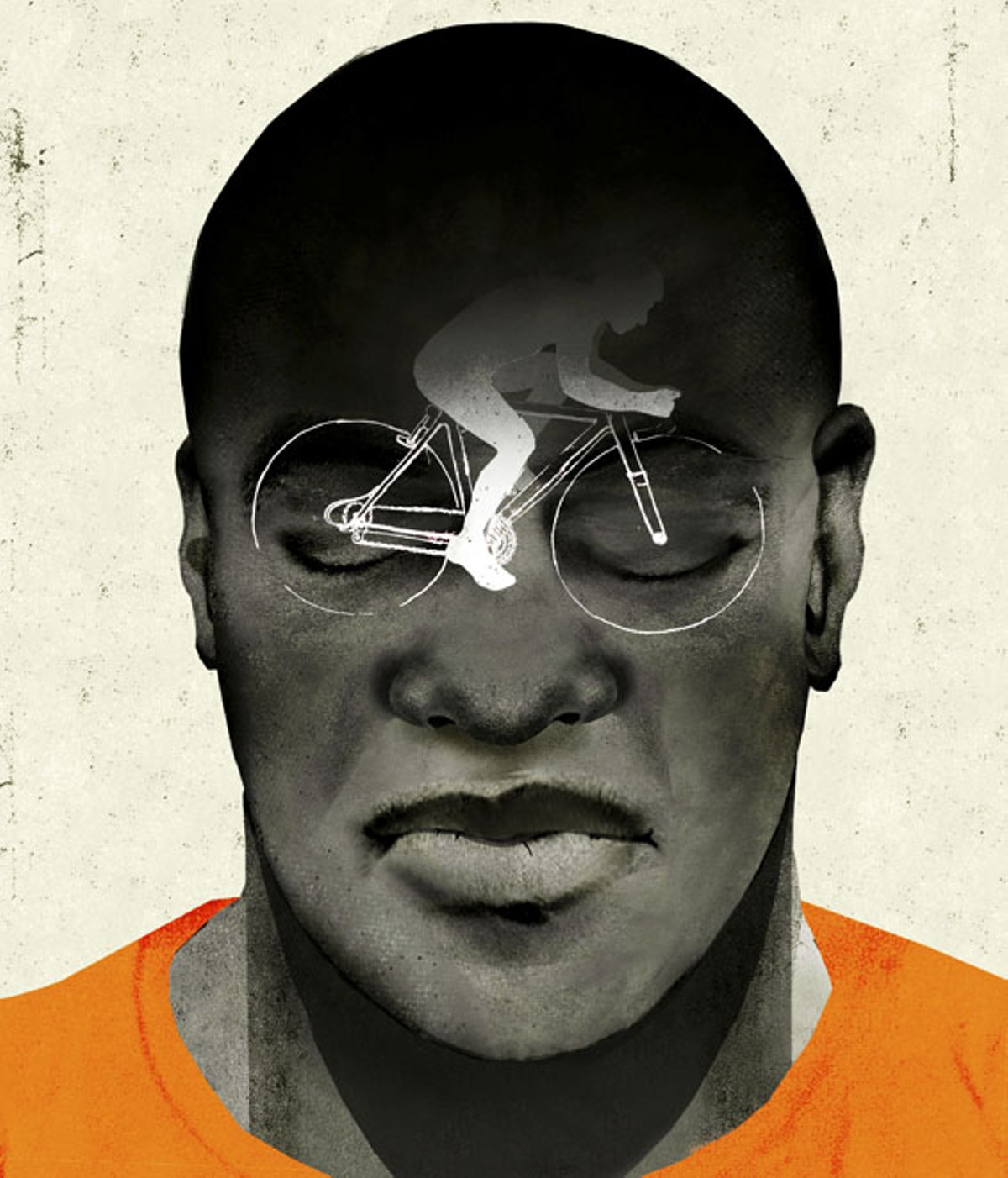

Dorian Williams has been diagnosed with "delusional disorder, grandiose type." Though he's never competed in any race, he believes himself a world-class track cyclist. In the language of the most current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, his is a "conviction of having some great (but unrecognized) talent" that is "clearly implausible."

This disorder is "relatively rare in clinical settings," write the DSM authors, adding that precise stats are "lacking," but likely less than 0.03 percent of the population suffers from it.

Doug Burris, chief U.S. probation officer of Missouri's Eastern District, says he's come across 9,000 offenders in his seventeen-year career. "I've seen fewer than ten with that diagnosis," he says.

A "grandiose delusion" is a serious mental illness but isn't menacing by itself, experts say. Certain mental illnesses do correlate with violence, but they don't cause it. In fact, most people with serious mental illnesses never act violently.

Then there's Dorian Williams. Over the past decade he has been locked up repeatedly for threatening to murder those he believes block his path to greatness, including federal officials.

He has never perpetrated any physical violence — perhaps because authorities have foiled his plots in the nick of time, or because he never intended to carry them out. But either way, he ties up public resources by entangling himself in a criminal-justice system that, despite 23 years of contact, can't seem to extinguish his menacing behavior.

Compounding the problem is that Williams denies his condition and refuses treatment — a common situation for people struggling with severe psychoses, according to Ira Burnim, legal director of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, a nonprofit in Washington, D.C., that advocates for offenders like Williams.

"We don't need him to admit he's mentally ill," says Burnim. "We just need him to change his behavior. If he's really, really exceptional, maybe you just have to find people who are especially skilled."

Williams hasn't found that level of care in the long term.

He was thirteen when his mother placed him and his twin sister into foster care. Court records state that the siblings were throwing house parties while their mother worked night shifts as a nurse. The home was broken into six times. Denise blamed "associates of her children."

(Neither Dorian Williams nor his family members responded to interview requests from the RFT.)

At some point in the late 1980s, Williams spent 40 days in psychiatric inpatient treatment. Court records don't specify why, but they do show that he was thrown out of two different youth shelters — once for threatening a kid with a pellet gun.

By age twenty, Williams had pleaded guilty to three felonies — stealing, burglary and credit-card fraud. He'd also been charged with (but not prosecuted for) third-degree assault, passing a bad check and hindering prosecution.

During these interactions with the law, he began to fudge his identity. He once told police he was a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. Another time, he listed the U.S. Marine Corps as his employer. Then he grew bolder.

On August 25, 1995, Williams walked into the Marine Corps base at Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. He introduced himself as Captain Dorian Williams and presented a fake ID. He tried to requisition a truck but wound up arrested. Williams later pleaded guilty in federal court to impersonating a military officer. He served three months in prison before being released on probation.

In between his stints behind bars, Williams conjured up a new identity — his grandest yet.

To this day, Big Shark employees recall Dorian Williams' muscular, spring-loaded frame. Clean-cut in cardigan sweaters, he spoke calmly and fluently about high-end gear. Big Shark owner Mike Weiss "vividly" remembers his initial purchases, paid for with cash: a Scott triathlon bike and matching Scott jersey.

"He was very concerned about aesthetics and bundling himself like a sponsored athlete," says Weiss, who became Williams' confidant. Weiss can't remember who brought it up, but the pair began discussing a black cycling legend from a century ago named Major Taylor.

Major Taylor broke the color barrier on two wheels decades before baseball's Jackie Robinson ever swung a bat. Blessed with bulging thighs and tactical shrewdness, Taylor set numerous records on the track and rose to world champion in 1899 — despite the schemes of racist bureaucrats and elbow-throwing white riders.

But if Jim Crow America never gave Taylor his due, the French greeted him like the messiah when he arrived in Paris in 1901. Aristocrats and tycoons jostled to socialize with the 22-year-old from Indianapolis. He toured European capitals, racing and earning a fortune.

"Dorian wanted to reenact Major Taylor's story," Weiss says. "That ultimately became the script." Williams felt depressed and persecuted by white authority, Weiss recalls. He saw cycling and Europe as his salvation, and Weiss didn't discourage him.

"Not that we're all that heroic selling bikes," Weiss says. "But we help people discover a sport and sometimes their new identity." So Weiss steered him toward Tim Kakouris, a Big Shark employee and skilled racer. Kakouris remembers him well.

"He'd always start off really earnest and intrigued," Kakouris says. "But once you started telling him what he'd have to do — get some miles in, get coaching, look at new equipment — he would get easily distracted, and it would degenerate into, 'I'm gonna be the fastest there is.'"

Strange reports started trickling into the shop. Cyclists out on training rides in Forest Park were having encounters with a belligerent rider. He'd pedal up to them and cut them off, or try to badger them into an impromptu race.

Back inside the shop, Williams began showing hostility to employees — even other customers.

"He'd get closer to you, shoulders forward, arms back," Kakouris says. "He'd say, 'So what, you think you're faster than me? You wanna fight me?' He looked like he might want to throw a punch." Weiss escorted him outside on one occasion to calm him down.

"The frequency of our interactions was increasing," Weiss says, "to the point that we were getting quite uncomfortable. Then suddenly, it ended."

Like many mentally ill offenders, Dorian Williams strayed from the path set out by his probation officer. After serving a few months in 1996 for impersonating a military officer, he was released but quickly violated his probation. So a judge sent him back to the slammer for eight months. He ended up staying eight years.

When Williams first arrived at the federal prison in Milan, Michigan, during May 1997, he informed staff psychologist Dr. James R. Tabeling that he'd already reached pro cycling status.

Tabeling described the patient as "quietly rageful," someone who construed all staff actions as insults. Williams singled out for special contempt a woman in the education department who urged him to earn his GED. He vowed revenge on her and "stated he had no choice."

By October, with his sentence winding down, Williams appeared to have stabilized. Still, Dr. Tabeling had his doubts. On October 8 he typed up a memo warning that his patient struggled to hold in rage whenever reality conflicted with his fantasies.

"[He] will most likely hurt the first person on the street that damages his view of himself," the doctor opined.

Despite that warning, Williams walked out onto the street a week later, a free man.

Meanwhile, back inside FCI-Milan, an inmate was causing alarm. He relayed to investigators that for days Williams had been muttering about several people involved in his conviction, including an FBI agent, a federal prosecutor and U.S. District Judge Donald Stohr of St. Louis.

Williams planned to "blow their heads off and kill their families," the snitch said, and was "knowledgeable" and "crazy enough to do it."

The following day U.S. marshals caught up with Williams and arrested him during his bus ride back to St. Louis. Prosecutors charged him with four counts of threatening to kill a federal official. A jury convicted him in August 1998. (He later admitted in court to making the threats.)

His new sentence stretched through 2001, to be served at FCI-Greenville in Illinois. This time, doctors noted, he was more "guarded" with psychiatrists.

He sat through only one counseling session at Greenville, then quit. After complaining of wrenching headaches, distrust of others and suicidal thoughts in May 1999, he received a prescription for the antidepressant Zoloft. Yet he wouldn't take the pills.

"Dorian is a very unique case in the extent to which he refuses services," explains Patty Barker, a U.S. probation officer who worked with Williams. He's very sharp, she observes, and most of the time, too high functioning to be institutionalized or forcibly medicated. But left on his own, she says, "he's a risk to society."

By late 2000, Williams was preparing to be released once again. He'd made it through his final sixteen months mostly drama free.

But then on January 8, 2001, officials searched his cell and found a typed list showing the following: "1 tetranito page 130, chlorhydric acid page 135, nitrochloroform page 747, chemicals for backup, ammonia, diesel fuel, nitro."

These are bomb-making ingredients — two of which, it was noted, had been used to great effect by Timothy McVeigh.

Federal prosecutors rarely try to lock citizens into hospitals for involuntary psychiatric treatment. In Dorian Williams' case, however, they felt compelled to.

Aside from his bomb recipe, his delusions had mutated. He'd been penning letters to potential biking sponsors, boasting of plans to break the hour time-trial record on a velodrome in Germany. In one letter he claimed to be a former member of the South African cycling team languishing in rehab. A Ku Klux Klan member, he explained, had plowed him over with a truck.

In July 2001 Dr. Carlos Tomelleri, a government psychologist, testified in a hearing that Williams' cycling delusions were "probably only the tip of the iceberg." The patient's "antisocial personality," he said, was "very clear." Tomelleri recommended that Williams be involuntarily committed because he had a mental defect that rendered him dangerous to society. The two other panelists agreed.

In 2001 Williams was admitted to the federal medical center in Springfield — the same facility where Jared Loughner, the man who tried to assassinate Arizona congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, is now under careful watch.

After only three months in treatment, orderlies had to isolate the 26-year-old Williams, citing "allegations he was taunting and antagonizing other inmates, especially the more severely mentally disturbed."

But by March 2002 he seemed to have turned a corner. He made "good contributions" to group therapy sessions, the panel noticed, and was giving the practice of meditation a try. Both his father and mother visited him in Springfield and offered to lodge him upon his release.

For the next several years Williams drifted between prison and halfway houses. In 2004, his probation officer found a knife on him and sent him back behind bars. But at last, in June 2005, a psychiatric panel deemed him "potentially dangerous, but not due to a mental illness." The federal government could no longer keep him institutionalized. So they let him go.

The record is silent on what happened to Williams for the next three years.

"Maybe whatever triggers his problematic behavior wasn't triggering it during that gap," speculates Ira Burnim, the mental-health advocate who learned of Williams' case from the RFT. "It's possible that he really is just totally out of his mind. But there just aren't that many people like that. There may be ways in which you could work with him."

When Dorian Williams swung open the front door of Big Shark in late 2008, owner Mike Weiss recognized him right away.

Williams carried a folder of letters. He'd written to cycling federations in Brazil, Germany and elsewhere, requesting that they host his attempt to break the hour record. They'd all declined, writing back that he needed a reference from his home federation, USA Cycling.

During Williams' time in prison, Weiss had become that reference as the local representative of USA Cycling.

"He thought that I stood in his way," recalls Weiss. "He completely disregarded the fact that the way you advance through sport is achievement — you have to move up the ladder. He just wanted to be installed at the high end."

Any progress he'd made seemed to have evaporated. On January 14, 2009, Williams threw a fit inside Big Shark. A store employee told him that a shirt he wanted was out of stock. According to the police report, Williams began to "yell and scream." He got within inches of the employee's face, instructed him to find a pistol in order to make it a fair fight, then walked out.

In March 2009, Williams blew up again over an order, this time at Heads n Threadz, a clothing store on the opposite end of the Loop.

That evening, an "Alex Williams" called the retailer, warning that his brother Dorian had stolen his carbine-style rifle and was headed to the shop to "take care of business." A clerk who answered the phone told police that the caller might've been Dorian himself. Officers shuttered the shop for the night.

By the spring of 2009, USA Cycling officials in Colorado were experiencing their own strange encounters with Williams. On their website, someone opened an account under "Dorian Williams," then immediately requested a name change to "Alex Devoure." In the box marked "Reason," the user typed: "Security concerns."

Around this time the federation's chief operating officer, Sean Petty, received an e-mail from a Dorian Williams alleging racism in the licensing process. At first, Petty — who declined to be interviewed for this story — feared negative publicity from a discrimination lawsuit, Weiss recalls.

Weiss concedes that "99 percent of the peloton is white." But that can't be by design: Nowhere does the license application even address race. USA Cycling couldn't discriminate if it wanted to.

Nevertheless, Williams e-mailed Petty to inquire whether an athlete may bring armor-piercing rounds to a race. Then he asked if physical confrontation was the only solution to his problem and hyperlinked to an article on Charles "Cookie" Thornton — the Kirkwood resident who felt that he, too, was a victim of racism and shot to death six people at a city council meeting.

"It wasn't a direct threat," says Weiss, who saw a forwarded copy, "but it was so ominous." The shop owner felt USA Cycling officials now lay in the crosshairs — especially after recalling that Williams had recently complained that airport cops arrested him while he tried to travel to Colorado for his license.

Alarmed, Weiss called Petty's cell phone to warn him. Petty answered high up in the mountains on a ski trip.

"Trust me when I say this," Weiss remembers telling him. "We've got a Columbine-type character here. I'm not safe, you're not safe, and your staff is not safe." But Petty didn't share the concern.

In early summer 2009, Williams walked into Big Shark with a backpack. Weiss glanced inside and believed he saw a gun. The visit ended peacefully, but it rattled the shop owner.

Weiss surfed around online and came across a profile that Williams had set up on Hookit.com. He'd listed himself as a cyclist and posted a photo of himself in a decorated military uniform, next to the following quote by Benjamin Franklin:

"Life is a kind of chess, in which we have often points to gain, and competitors or adversaries to contend with, and in which there is a vast variety of good and ill events, that are, in some degree, the effect of prudence, or the want of it."

Mike Weiss had just opened his eyes on the morning of July 8, 2009, when his cell phone rang.

"Where are you?" asked Phil Green, a childhood friend of Weiss' and a St. Louis police officer.

"I'm in bed," Weiss said.

"Are you OK?"

"Um, yes," responded Weiss.

Green instructed him to stay put. Officers were en route. They'd received an anonymous tip that, at 10 a.m., a man named Dorian Williams planned to gun down Weiss.

Patrolmen collected the shopkeeper and brought him to the police station, where Capt. Sam Dotson debriefed him. Cops were hunting for Williams. In the meantime, the force could only spare one officer to guard the shop for two days. Thousands of baseball fans were converging downtown for the All-Star game. President Obama was throwing out the first pitch. Manpower was scarce.

Back at Big Shark, frightened employees threatened to quit. Desperate, Weiss paid a visit to the cramped office of private investigator Kevin Burgdorf, just south of Forest Park.

Burgdorf, a retired city cop with a Fu Manchu mustache, agreed to provide security. Weiss asked if he could start right away. Within an hour, a TV news crew was arriving at Big Shark to interview Weiss about the governor's decision to end funding for the Tour of Missouri race.

"So Burgdorf opens this drawer in his office," Weiss says, "and pulls out all these firearms. He's putting them in his shoulder holster, and foot holster and his belt. And he drives me to this interview, and he's just hanging out in the street, looking around."

For two weeks Weiss paid two plainclothes guards to linger in the shop during business hours. Weiss also applied for an order of protection against Williams. Burgdorf agreed to serve Williams the papers. But he needed to track him down first.

He visited the home of Williams' father, James, in the Ville neighborhood. As Burgdorf remembers it, the first thing out of James Williams' mouth was: "What did he do now?"

The father, a laborer at Boeing, seemed skittish, Burgdorf recalls, because the cops had already come twice brandishing firearms, looking for Dorian.

Williams Sr. said he'd neither seen nor spoken to his son in weeks.

At the bike shop, police officers asked Weiss whether he owned a gun.

"I'm a pacifist," Weiss said. "I don't have a gun. I have a cat." But one officer — Weiss won't disclose his name — discreetely lent him a 9mm handgun with a chambered round. Weiss carried it with him, even in his car.

"I thought the charade had gone too far," Weiss says. "So I was resolved that if [Williams] showed up, I was just going to shoot to kill.

"It's hard for me to say that," continues Weiss, a quiver in his voice. "But the logical side of me said, 'His anger at you is irrational; you've done nothing to this man. This person is calling in death threats. The only stupid thing is to try to reason with him.'"

Records show that police caught up with Williams in August 2009 in St. Louis County. They issued him a summons to appear in court for disturbing the peace at Big Shark. But once again he was eventually let back on the street.

Five months later — in January 2010 — came the call about a "Dorian" who may "possibly" be carrying explosives onto a Continental flight. Cops thought they glimpsed Williams at his mother's house in March 2010, but whoever it was vanished.

Then, for several months, Dorian Williams disappeared again.

On August 4, 2010, Sgt. Robert Almada of the Santa Monica Police Department in California received an anonymous tip. A Dorian Williams — wanted by the FBI — was loitering by the chess tables on the beachfront.

Almada arrived on the scene and spotted Williams, leaning against a railing and looking out toward the sea. Williams noticed Almada approaching.

"I was watching his hands," the sergeant later testified. "His hands were gripping the railing tighter and tighter, and he was starting to kind of flex his hands a little bit, which made me a little nervous."

A few feet away, Almada said, "Dorian, you're under arrest."

Williams whirled around, clocked Almada in the face and said, "I'm not Dorian."

He bolted, but Almada tackled him in a parking lot, shouting, "Police, police, get on the ground!" But the suspect scrambled free and sprinted off, weaving in and out of the crowd. Other officers, alerted by radio, finally nabbed him half a mile away.

A search of his person revealed photos of him in a military uniform and a slip of paper on which was scribbled the phone numbers of two St. Louis-based defense attorneys and a third number — the cell phone used to make the bomb call to Lambert.

Santa Monica police transferred Williams into federal custody then sent him back to St. Louis.

While awaiting trial, Williams filed a handwritten motion to the court, requesting military-issue MREs ("meals ready to eat"). He feared that prison staff, "acting as vengeful mercenaries," might poison his food.

Williams' trial this past July lasted just two days. The jury heard the tape of the bomb threat. They compared that to the taped conversation between Williams and the airport detective pretending to be with the Missouri Bicycle Racing Association.

Jurors deliberated for a little more than two hours before finding Williams guilty on one count of conveying false information about bombing a commercial aircraft and one count of conveying a threat and false information about destruction by explosives.

Williams may have qualified for an insanity plea. Other criminals with mental disorders, such as Ronald Reagan's would-be assassin John Hinckley Jr., have deployed a similar defense to avoid prison. But Williams didn't take this route. His court-appointed defense attorney, Diane Dragan, filed a motion to have Williams' mental health evaluated but later withdrew it.

At his November 21 sentencing, though, Dragan did indeed broach the subject of his mental health.

"In many ways, Mr. Williams' case is an example of our criminal-justice system being used to treat mental illness," Dragan told the court. "There are problems that the Bureau of Prisons is not going to be able to treat."

Cloaked under baggy corrections garb, Williams at 36 still looked focused, lean, athletic — much like a cyclist. He barely spoke before the judge. Only his face betrayed emotion: a continuous sneer.

Dragan's plea for lenience did not sway U.S. District judge Henry Autrey, who agreed with assistant U.S. attorney John Sauer that Williams qualified as a career offender and should be imprisoned.

Williams is appealing his case and waits inside the St. Louis County Jail in Clayton. If he loses the appeal, his sentence of eight years stands, putting him back out by 2020 at the latest. And, if history is a guide, the cycle will continue from there.

"He doesn't fit into any existing places," laments Williams' former probation officer, Patty Barker. "It's a no-win situation. We almost have to wait for him to commit another crime."